Issue Date: April 18, 2003

U.S. foreign policy today: Zealotry triumphant Captain America and the Crusade against Evil: The

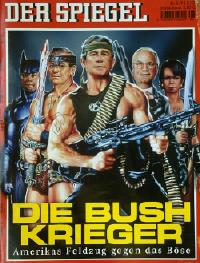

Dilemma of Zealous Nationalism Reviewed by JAMES FREDERICKS The Feb. 18, 2002, cover of Der Spiegel caught the attention of Daniel Coats, the U.S. ambassador to Germany. The cover depicted “the Bush Warriors” (die Bush Krieger). Colin Powell was portrayed as Batman, Donald Rumsfeld as Conan the Barbarian. Dick Cheney was depicted as the Terminator, flanked by Condoleezza Rice as Xena, the Warrior Princess. The president himself was given pride of place in this band of warriors as Rambo, in the classic pose with a bandoleer draped manfully over his chest. Coats asked Der Spiegel to supply poster-sized copies of the cover for the White House, confirming European perceptions of America as a place that has been inoculated against all forms of irony by the sheer success of its own pop culture. Robert Jewett and John Shelton Lawrence agree that we have a Rambo in the West Wing. More interesting, they argue that the roots of the superhero myth that guides policy today can be traced to the Bible. In making their case, Jewett and Lawrence succeed in placing the discussion of American civil religion on a new tack. In their view, American civil religion is the troubled repository of two incompatible tendencies: zealous nationalism and prophetic realism. Zealous nationalism sees America as a “city on a hill,” set apart by God from the other nations, as a chosen people with a sacred duty to preserve and protect democracy against all comers. The zealous like to think of foreign policy in apocalyptic images. Political complexity and moral ambiguity is reduced to a more easily managed duality: light vs. darkness; good vs. evil; innocence vs. depravity. Since God’s chosen are threatened by conspiratorial evil, violence in defense of the nation takes on the sacred quality of a redemptive act.

Jewett and Lawrence have considerably less to say about prophetic realism. Like zealous nationalism, this side of American civil religion has biblical roots. The preaching of Amos and Hosea, to give two obvious examples, undermines the unnerving certitude of the zealous. The Day of the Lord will not be a time of vindication, but of judgment. The covenant requires the nation’s moral reform. The enemies of God lie not beyond the nation’s borders. Pogo got it right. For the zealous, compromise means flirting with apostasy. Prophetic realism allows for political horse-trading as an alternative to Armageddon. Jewett and Lawrence, not surprisingly, place Jesus of Nazareth in this tradition of prophetic realism. The kingdom of God comes through metanoia, not sacralized violence. The Law requires us to love Samaritans, not bomb them back into the Stone Age. In Italy, life imitates opera. In America, life – especially political life – takes its cues from comic books. This brings us to the “Captain America” of the title. In this 1941 story, Steve Rogers is rejected as physically unfit for military service. Concerned that every 90-pound weakling should get his chance to save the world for democracy, a scientist transforms Rogers into a buff crusader who has not only the biceps but the chutzpah to save America from the forces of darkness. Jewett and Lawrence, like Der Spiegel, know an apocalypse-crazed superhero when they see one. The American superhero provides an archetypal narrative for the politics of zealous nationalism driving American foreign and domestic policy. Americans like their superheroes to be loners who serve the values of democratic society while not fitting comfortably within it. Bruce Willis in the “Die Hard” movies and characters from Westerns like “Shane” and “The Virginian” are examples of such civic-minded misfits. Sometimes, like Superman, they are actually aliens who disguise themselves as a mild-mannered reporter in order to rub elbows with a sexually frustrated Lois Lane. Other times the superhero is a perfectly ordinary Joe, like Charles Bronson or Rambo, who rise in sacred rage, like Viking berserker after an encounter with evil. Despite all the heroics, the superhero myth displays a surprising pessimism about our democratic institutions. Democratic institutions may be able to protect our youth from threats like Catcher in the Rye, but they are helpless before the power of conspiratorial evil. So, in defending America from the forces of darkness, the superhero has no qualms about going outside the law. America’s fascination with vigilantism links the mythos of the superhero with the redemptive violence of the apocalyptic worldview. Democracy cannot protect itself from forces of cosmic evil, but the superhero, because of his unimpeachably pure motives, is able to engage in violence without being corrupted. The analysis of the presidency of Ronald Reagan makes one wonder if his policy advisers moonlighted as copy editors for Marvel Comics. This self-described “non-political person” -- a regular guy who would rather be back on the ranch mending fences -- came to power with a plan to save America from an “evil empire.” The Strategic Defense Initiative, whose unstated apocalyptic agenda still mesmerizes the zealous, was soon dubbed “Star Wars” by its critics. Reagan is reported to have liked the moniker -- the good guys win the battle at the end of the movie, don’t they? The defense of helpless democracy eventually led to the administration’s jumping the rails of legal decorum. In direct defiance of the U.S. Congress, Oliver North, a Marine working with Reagan in the West Wing, sold arms to Iran’s Islamic government in order to fund the “freedom fighters” in their attempt to bring down the government of Nicaragua. In defiance of international law, Reagan mined Nicaragua’s harbors, which made necessary America’s withdrawal from the World Court. In recent weeks, several commentators have pointed out that George W. Bush’s political DNA comes from Reagan more than George H.W. Bush. George W.’s unilateralism and terrifying certainty about the world look more like Reagan’s crusade against communism than George H.W.’s pragmatic multilateralism. On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, this ordinary guy from Midlands, Texas, suddenly realized he had to set out on a “crusade” (his term) against terrorists. Reagan’s “evil empire” was soon transmuted into a battle against an “axis of evil.” According to David Frum, a former Bush speechwriter, “axis of evil” is the President’s own term of art. Frum originally proposed “axis of hatred” to his boss. “Hatred” got the red line. The substitution reveals much about how George Bush makes religious sense out of the world. The man’s credentials as a sincere evangelical Christian are beyond dispute. Accepting Jesus in his early 40s led him to put down the Jack Daniels and reach for a Bible. Instead of AA, Bush attends Bible study groups. During his father’s campaign for president, he served as liaison to Reagan’s friends on the religious right. This is a decidedly apocalyptic bunch, supporting not only Reagan’s crusade against the “evil empire” but the religious extremists who have hijacked Zionism as well. The issue, of course, is not Bush’s evangelical faith (Jimmy Carter was an evangelical), but the religious zealotry that propels the foreign policy. In his speech to a joint session of Congress after the terrorist attacks, Bush made clear what this fight is all about: “Freedom and fear, justice and cruelty have always been at war, and we know that God is not neutral between them.” According to Frum, Bush wanted “axis of evil” and not “hatred” because this theological move would do much to cut off any discussion of whether America might need to reconsider its behavior in the world. In this lies the triumph of zealous nationalism over prophetic realism. “The liberty we prize is not America’s gift to the world,” Bush assured the nation in the State of the Union address; “it is God’s gift to humanity.” America, however, has a special role to play in the drama of redemption, since “our nation is chosen by God and commissioned by history to be a model to the world of justice.” Jewett and Lawrence can be prolix at times. I would like to read less about how zealous nationalism accounts for most of American history and more about how prophetic realism might help us to dis-enthrall ourselves from our zealotry. The authors also oversimplify American civil religion by limiting a choice between nationalism and realism. Dualism is infectious, I guess. Their factoring of American civil religion into these two alternatives can bear neither the full weight of American history nor of biblical theology. Even with these hesitations, the book is very timely. “The worst vice of a fanatic,” Oscar Wilde once noted, “is his sincerity.” The sincerity of American zealotry cannot be in doubt, especially today. Now, in a spirit of prophetic realism, we need to ask, who will save the world from those who would save America? James Fredericks teaches theology at Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles. National Catholic Reporter, April 18, 2003 |