Issue Date: May 16, 2003

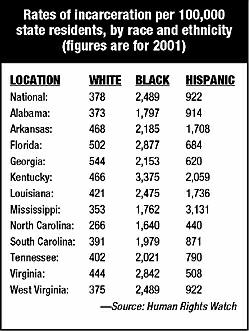

2,000 activists from across the South challenge the system First in a series By LILI LeGARDEUR The prison portraits flapping from the windows of Craig Elementary School were a cheery study in blues, reds, yellows and third-grade imagination. A close look, though, revealed their troubling content: a dark-skinned man with a headband hemmed in by prison bars; a sad-faced woman framed by the words “I miss you, Anti,” a group of smiling children next to a woman with bars across her face. “On the opening day of Critical Resistance South, we are asking a question of this country of ours,” intoned conference organizer Melissa Burch, gesturing over her shoulder at the portrait-bedecked public school. “Why are so many people we love behind bars?” Burch spoke at a news conference opening Critical Resistance South: Beyond the Prison Industrial Complex, a regional gathering that drew more than 2,000 critics of the burgeoning U.S. prison system to the Treme neighborhood of New Orleans during the weekend of April 4-6. Her words introduced a major report detailing the impact of imprisonment on the South, where incarceration rates exceed the national average by 12 percent (see chart below). For those impervious to statistics, though, the kids’ paintings made two key points of the report painfully clear -- that imprisonment breaks up families, and that it has a disproportionate impact on poor African-American communities like Treme. Critical Resistance is a national grassroots organization devoted to ending the “prison industrial complex,” which activists see as a collusion between industry and government ( See accompanying story)

The three-day gathering officially opened with a rally headlined by former Black Panther Angela Davis, who urged those present to make a connection between protesting the prison industrial complex and fighting against both the U.S. war in Iraq and the USA Patriot Act. More than 100 workshops over the next two days brought lawyers, ministers, social workers, former prisoners, prison family members and students together to share information about the state of the prison industrial complex and inroads being made against it. Questions of personal responsibility, guilt and innocence -- ideas that normally dominate criminal justice forums where prisoners or former prisoners aren’t leading the discussion -- were notably absent from the weekend, although several meetings looked at restorative justice and other means of reintegrating both offenders and victims of crime into society. Instead, the emphasis was on critiquing a system that tracks poor and especially black men and women into prisons at astronomical rates, giving a young black man in the South odds greater than one in four of spending time in prison. “Do prisons make us safer?” asked Jason Zeidenburg of the Justice Policy Institute, author of the report “Deep Impact: Quantifying the Effect of Prison Expansion in the South.” Zeidenburg answered his question: “Four national studies say maybe, maybe not. Louisiana added twice the prisoners to the system that Florida did in the 1990s, but Florida had a bigger drop in crime.” Dan Horowitz de Garcia, program director of Project South in Atlanta, spoke more sharply. “The Southern drive to put people in cages is not an answer to our social problems,” he said. “Security comes from respect for human rights, quality education, jobs. Security comes when we get what we need to control our lives.” In fact, the Bureau of Justice Statistics Crime Victimization Survey for 2002 indicates that violent crime is at its lowest level in the United States since 1974. At the same time, mandatory sentences, primarily for drug-related offenses, have filled the prisons with criminals who 20 years ago would not have served time. Between 1990 and 1998, more than 1.5 million first-time offenders entered state and local prisons on drug charges -- and, because of truth-in-sentencing laws popularized in the mid-1990s, they’ve stayed there longer. As Ryan King, research associate for The Sentencing Project, puts it, “They’re flowing in at a steady rate, but they’re not flowing out at a steady rate.” Today, the average sentence for a first time, nonviolent drug offender is longer than the average sentence for rape, child molestation, bank robbery or manslaughter. One person who was caught up in the sentencing laws was Dorothy Gains, who spoke to the conference’s opening night gathering. A mother of three, Gains was sentenced to 19 years in federal prison in 1993 on charges of conspiracy to possess and distribute crack cocaine. President Clinton pardoned her before leaving office in 2000. “I was sentenced to 19 years in federal prison because I refused to snitch and do the government’s job,” said Gains. “This happens because so many of us are willing to sell out one another for ourselves.” Gains put a human face on an analysis that many say dodges the harsh reality of crime and the need for punishment. So did Robert “King” Wilkerson, the Black Panther who spent 29 years in solitary confinement as one of the Angola 3 before being acquitted and released in 2001. Wilkerson drew a standing ovation from the crowd at the Friday night assembly, where he read a statement by fellow Angola 3 prisoners Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace, both of whom are still being held in solitary confinement in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. Patrick Banks, the youngest activist to address the assembly, talked about his time in a juvenile detention boot camp in Florida. Charged with grand theft auto for driving his father’s car, Banks was beaten by guards and suffered a broken leg. When his father died, prison authorities denied him a furlough to attend the wake. “If nobody shows they care, where are we actually going to go?” asked Banks. “If rehabilitation is beating us up, what are we going to do when we get out?”

Davis, whose 1998 essay “Critical Resistance: Beyond the Prison Industrial Complex” lent the conference its name and addressed its opening session. “It is incumbent upon us to articulate our work against the prison industrial complex,” she said, using the driving, staccato delivery that has made her a forceful speaker since the 1970s. “It is incumbent upon us to articulate our position against this war and the military industrial complex and against Patriot Acts I and II.” She also said those present should link the attack against affirmative action with their work against the prison industrial complex, saying that educational policies played a major role in tracking young blacks into prison. The call was timely, since the U.S. Supreme Court just that week had announced its decision that the University of Michigan’s “race-sensitive” admissions policies were unconstitutional. “How many young black men and women will end up in the military because of this?” she asked, adding that many of her friends from her hometown, Birmingham, Ala., had gone into the military to avoid prison. Jerome Smith, a civil leader who has run the Treme Community Center and worked intensively with youth here for more than 30 years, brought the discussion back to Treme and the present. “The classrooms across the street are crowded,” he said, talking about conditions at Craig Elementary, whose students painted the prison portraits. “There are termites at McDonogh 15 [elementary school]. And they’re going to rebuild Iraq?” Smith introduced five youngsters from the youth organization Tambourine and Fan, who recited the lyrics to the jazz ballad “Strange Fruit” in military unison. Tarik Smith II, Jerome Smith’s 12-year-old grandson, transfixed the audience with a three-minute drum solo that was a paean to freedom. ‘We believe in linkage,” Jerome Smith said as the drumbeats died away. “Our children are a great treasure, but we believe in linkage and when they say and recite “Strange Fruit” they know how to put themselves up.” The focus on the children -- five young people who have not been incarcerated, but who certainly, by the odds, have a parent or sibling or friend in the system -- gave resonance to something another speaker, Vin Diehl, had said earlier. “We’re tired of them taking from public education. They allow drugs and guns to flow free. What they want is what you call legal slavery,” he said. “What people need to be asking is, what does restorative justice look like? What does an education system that does what people need look like?” Lili LeGardeur writes from New Orleans.

National Catholic Reporter, May 16, 2003 |