|

Issue Date: May 16, 2003 America through European eyes A professor traveling in Italy is startled to discover the change in the U.S. image By MARIA J. FALCO I was watching Italian TV and seeing something I had never expected to see in Italy: a Catholic priest leading a group of antiwar protesters surrounded by banners identifying some of the activists as communists and other left-oriented party members, as well as students and pacifists. They were standing on the train tracks in Pisa to prevent U.S. Armed Forces trains from shipping war materiel from the port to the base in Vicenza, adjacent to the Adriatic from which these armaments would be shipped to Turkey or the Persian Gulf. This was not a Daniel or Philip Berrigan I was watching but a mainline Catholic chaplain, in tune with the clearly enunciated antiwar policy emanating from the Vatican, denouncing a war that had yet to begin. It was as though someone had stripped off the sock from the Italian boot to reveal the exact reverse image of what I had known as a student in Florence 49 years earlier, except that the common enemy was not the Soviet Union but the United States! I watched these “Disobedients,” as some conservative politician had dubbed them, for several nights in a row succeed in their efforts until someone in the American military command decided to move the trains at 3 a.m., thus ending the confrontation peacefully. But what was even more surprising was that nowhere on CNN or in the American newspapers that I could find (primarily, the International Herald-Tribune) was there any coverage at all of this, in my eyes, somewhat historic development: the Catholic church joining up with the parties of the “left” to confront the United States over a matter of foreign policy. I had returned to Italy in mid-February for a number of reasons, one of which was to revisit some of the historic and artistic sites I had seen over the years to gain new perspectives on their meaning and impact on our modern and postmodern world. I certainly did not expect to see the incredible changes in political perspectives that appeared to have been brought about in two short years by events in the United States and the Middle East.

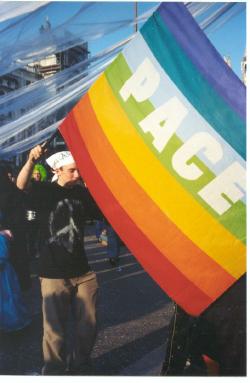

A case in point: The directress of the convent where I was staying in Florence stopped me one day shortly after hanging a rainbow-colored “Peace” banner (PACE) in the reception room where mainly students, French, German and American tourists were greeted on their way to their rooms. “Tell me about George Bush,” she said, in an inquiring, nonconfrontational voice. Having just read Nicholas Kristof’s column in the Herald-Tribune, I told her he was a fundamentalist, evangelical Christian who tended to see things in black and white instead of gray and that, because Saddam Hussein was “evil,” the latter had to go. She responded, “But if [the president] is a good Christian, why doesn’t he listen to the pope when he says this war is wrong?” A few days later I was seated at a crowded small café next to my hotel in Venice eating a toasted sandwich for lunch when the proprietor asked if he could seat another couple at my table. They were from Dijon, France, and since neither of us spoke the other’s language very fluently, I jokingly gestured that our two nations were currently at odds over Iraq. The man then very seriously replied, “Oh, Madame, we are very much against this war. I served in the Resistance during World War II and I can tell you that war is a terrible thing.” Since he did not look old enough to have been in the Resistance during the war, I said nothing. His wife then said, “I experienced the bombings during the war and was so frightened, Madame -- it was terrible, terrible!” At this point all I could do was agree with them, and said, “Yes, I understand. My father was wounded in the battle of Nancy/Metz.” In retrospect, that may have been a cheap shot on my part, but it ended the discussion of Iraq and we went on to talk about other things like Dijon mustard and the Louisiana Purchase. Unfortunately, this point of view was not confined to the French. Increasingly, it became more and more evident that public opinion throughout Europe, Italy included, had become diffusedly directed against war in general, and this war in particular. On the day after George Bush made his speech announcing the imminent outbreak of the war, I informed the concierge of my hotel in Rome that I had been up until 2:30 a.m. watching him. A guest from the Netherlands asked, “To do what?” I replied, “To tell Saddam he had 48 hours to get out of town.” “Exactly,” the man replied, making a cowboy “gun-in-holster” gesture. An exception was the opinion voiced by a professor from the Second University of Naples (there are five in all), whom I met in Urbino. When I asked him who was more responsible for the seemingly impending break-up of the European Union and the devastating split in the United Nations, Jacques Chirac or George Bush, he replied, “Both are. France controls most of the oil in Iraq and America hates that!” Well, at least he was evenhanded in his response, I thought. There was other evidence of evenhandedness, or at least of an attempted balanced approach to the war. While driving from place to place throughout Italy, I came upon a talk radio station called “Radio Radicale.” Because of its name, I was amazed to hear not anti-American commentary but a sympathetic, while critical, series of broadcasts from various sources on this station. On one occasion I heard a French commentator with a voice-over Italian translation ask, “Where were all the antiwar pacifists when Saddam Hussein was killing all those Kurds and Shiites before and after the Gulf War?” The Americans are not monsters, he said, “but are suffering from the aftereffects of the Sept. 11 catastrophe.” But this sentiment appeared to be held only by a minority of those I heard. One very popular TV talk show called “Ballaro,” hosted by a youngish, rather sharp-tongued moderator, was a case in point. On one occasion he interrupted an American commentator so often it was impossible to get a clear idea of his point of view. On another the moderator actually prevented an Italian government minister from talking at all -- to great applause from the audience. And when a clip was shown with George Bush stating that the war would be fought to free the Iraqi people, he shouted, “Propaganda!” also to thundering applause. On the last of these weekly shows that I was able to view, there were three government ministers present plus one undersecretary, and finally one of them took the moderator to task for making a joke of a very serious matter. I am still not sure who actually came out ahead in this encounter, because, once again, his rather youngish audience appeared to agree with the moderator rather than with the graying government ministers. However, perhaps the most painful experience I had during my trip to Italy came from within the bosom of my own family. On the last Sunday before I left to return home to New Orleans, I was the guest at a feast my cousin worked for two days to prepare in my honor. One of those present was a relative of a relative who lived next door. Between courses in this rather long dinner, she opened up with an angry harangue against the Americans who were responsible for this terrible war. “All war is wrong,” she said, and this war was particularly wrong “because it was not necessary.” It is not worth all the lives of innocent women and children that will be lost as a result. At this point the professor in me leaped forth -- especially since other guests were chiming in around me. “Perhaps you’re right,” I said. “But for over 1,000 years not even the church held that all wars are wrong. The question is, is this a just war? But since I am not a moral theologian, just a political scientist, I can tell you only about the practical considerations that went into the decision to wage this war.” To summarize: The people who are saying that the war is not necessary are saying so because our troops stationed in Kuwait were the threat that made Saddam agree to some minimal responses to the U.N. inspectors and to the elimination of some very old missiles. But those troops could not be held there indefinitely, to satisfy the time requirements of the inspectors who wanted to pursue a gradual reduction of weapons instead of the “immediate” response as decreed by the United Nations last fall and over the past 12 years. When he committed our armed forces to a major buildup as a way to get Saddam to comply, George Bush placed himself in the position of having to move into Iraq or get out and suffer humiliation. It was a two-edged sword, I said. If he went forward, he would lose the support of moderates. If he went backward, he would lose all support at home. He brought some of this on himself when he announced that he would go it alone, if necessary, and that “if you were not for him, you were against him” -- something a diplomat never does. That comment served as a red flag before a bull, and apparently most of the world joined together to challenge him. When my adversary announced that I agreed with her then, I responded loudly, “No!” and went upstairs to get some aspirin. The discussion had given me a headache. I could not possibly agree with her first premise, that all wars are wrong -- the pacifist position -- but was this war truly necessary? It had reminded me of Thomas Friedman’s argument that this war was “optional but necessary” -- a conundrum, if I ever heard one. Because I left Italy before images of the cheering crowds of Iraqis tearing down statues of Saddam all over Iraq could be seen on TV throughout the world, I had no chance to revisit this conversation with my relatives or with anyone else I had spoken to during those six weeks -- nor even to see what the host of “Ballaro” would have to say about it. Back in this country, I watched on April 22 a presentation on Ted Koppel’s “Nightline” in which it was stated that the war on Iraq had not been fought to eliminate weapons of mass destruction after all. None had been found to date, and it looked as though none would be found. Instead, the threat from Iraq had been deliberately exaggerated by members of the Bush administration, including Colin Powell before the United Nations, in order to justify removing Saddam Hussein as a warning to all other regimes in the neighborhood that had flirted with, supported, engaged in, or otherwise encouraged terrorist activities against the United States throughout the world. Paul Krugman’s column carried the same story in The New York Times April 29. I find myself wondering, if this assessment is true, is lying to the world and to the American public and putting American, British and Iraqi lives at risk justified by our fears of another Sept. 11? I’d like to hear from the right and the left on this point -- from theologians Michael Novak, Jean Bethke Elshtain and James Gaffney, and anyone else who’d care to join in. Because I still have that headache I developed in my cousin’s kitchen March 30. Maria J. Falco is professor emerita of political science and former academic vice president of DePauw University in Indiana. She is the author and editor of five books. National Catholic Reporter, May 16, 2003 |