Issue Date: September 12, 2003

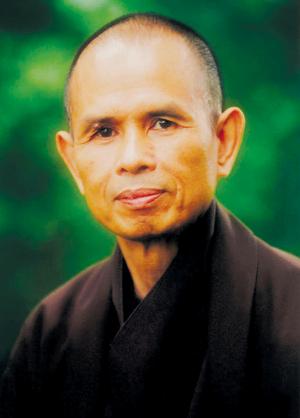

Famed Buddhist monk urges overflow crowd to live mindfully By HEIDI SCHLUMPF Five thousand people came to Loyola University Chicago on Aug. 22 to

hear Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh speak about peace, but instead

they actually practiced peace. Following the prescription in his new

book, Creating True Peace ( It wasn’t easy. Many people had fought Friday rush-hour traffic to arrive an hour early for the sold-out event, hoping to get good seats in the general-seating gymnasium. Upon entering, they were handed a note instructing them to quietly take their seats and enjoy silent meditation until the program began. Led by 80 brown-robed Buddhist monks and nuns seated cross-legged on the stage, they practiced “breathing in” and “breathing out.” With only the shuffling of sandals, the rustling of purses and the occasional cough, the “Home of the Ramblers” surely had never witnessed such stillness from so many people. Just as the dreaded “bleacher butt” was beginning to set in, the program began with a few more guided meditations and some hauntingly beautiful chant by the monks and nuns. After an organizer reminded people to turn off their cell phones, Thich Nhat Hanh himself invited the crowd to stand and led them in a few sorely needed stretches. Finally, the famed monk began to speak --but the audience couldn’t hear him. A combination of poor acoustics in the gym, a less-than-ideal speaker system combined with Nhat Hanh’s low voice and thick accent made his words unintelligible. Most reacted calmly, but several audience members angrily shouted out, “We can’t hear you” or worse, badgered him, “You need to speak directly into the microphone.” To which Nhat Hanh smiled and quietly said, “I’m sorry.” Hundreds began noisily descending the metal bleacher stairs to sit in the aisles or to leave the auditorium altogether. The irony of the situation was not lost on the audience, including Carrie Maus, who had planned for weeks to attend the event. “At first I was really frustrated, but then I started thinking there was a lesson here,” she said. “So I just focused on trying to be patient. The more I was able to be still, the better I could hear.” Such focus on the present moment and mindfulness is Nhat Hanh’s clarion call. “With mindfulness we are able to be fully present, fully alive,” he said. “When you breathe in, and you know you are breathing in, and when you breathe out, and you know you are breathing out -- that is mindful breathing. Mindfulness is knowing what is going on.” By consistently practicing mindful breathing and walking, people can learn to relax their bodies and minds and to better handle strong emotions such as fear and anger, the internationally acclaimed speaker said. “If you know how to pay attention to the rise and fall of your breath, you’ll be able to survive anything,” he said. Although peace begins with the individual, the collective energy of mindfulness practiced in community can transform the violence and hate in society, he said. “We have to learn the art of cultivating peace, as individuals, families, churches, cities and nations,” he said. “The practice of mindfulness helps us look deeply to recognize the roots of our affliction, our anger.”

At the root of such suffering is wrong perception, Buddhism teaches. Practicing peace requires removing one’s own wrong perceptions through compassionate listening. Nhat Hanh used the example of terrorists the United States currently sees as its enemy. That only Americans have suffered is a wrong perception that needs to be changed through deep listening to the terrorists, he said. “The practice of compassionate listening can transform communication. Then you water the seeds of love and compassion,” he said. “But if you allow the seeds of hatred and despair to be watered, you will suffer very much.” Moving from personal practice to the political, Nhat Hanh called upon religious leaders, the media and especially elected politicians to adopt the practice of peace. “Violence cannot solve the problem of violence,” he said to applause. “Violence cannot reduce the number of enemies or terrorists. It creates more hatred, more violence, more terrorists.” Recalling the useless suffering during the war in Vietnam, his homeland, he said, “If we continue the path of violence, we will repeat the same mistakes as in the past.” Nhat Hanh will have a chance to tell U.S. politicians that himself during a scheduled lecture on Capitol Hill and a retreat for members of Congress, their staff and families this month. Those appearances will conclude a monthlong visit to the United States that included stops in Boston, New York, Denver, Boulder and Chicago, as well as a retreat for law enforcement professionals in Green Lake, Wis. With 5,000 people and another 1,000 turned away, the Friday night Loyola lecture was by far the largest event. Earlier that day, Nhat Hanh spoke to incoming Loyola freshmen and their parents at the annual freshman convocation. For the 1,200 students -- most of whom had never heard of the monk -- his message to not delay happiness until they graduate or get their first job resonated with 18-year-olds anxious about leaving home for the first time. And his advice that money, power and possessions don’t guarantee happiness received a standing ovation. “The students were really impressed by him,” said Jesuit Fr. Dan Hartnett, a philosophy professor and organizer of Nhat Hanh’s visit to Loyola. Those freshmen will learn even more from his writings, as they will be required to read two of Thich Nhat Hanh’s books this school year as part of Loyola’s Shared Texts Program. Nhat Hanh’s message of “engaged Buddhism” has already inspired Loyola graduate student Kevin Buckley, a former seminarian who has practiced Buddhist meditation for five years. “I think he’s trying to correct the wrong perception the West has of Buddhism being totally individualistic,” said Buckley, 30. “After you work on your individual peace, then you take that and engage the world.” Hartnett, who worked for 20 years in Peru before coming to Loyola, also sees the value in combining contemplation with action. “I really agree with his call that peace has got to start with us, with our own lives. But he’s definitely got a social message, too,” Hartnett said. “It’s hard to work for peace without a spirituality. You get burned out.” That’s precisely what the members of Chicago’s United Power for Action and Justice would like to avoid. In early August, community organizers and activists from Chicago, Lake County and DuPage County invited a speaker from the Lakeside Buddha Sangha, a meditation group formed after Nhat Hanh’s visit to Chicago in 1991. The goal was to learn more about the monk’s teachings and to reach out to Buddhists in the community. “I learned a lot,” said Wendy Mospan, a member of Lake County United’s steering team, who also attended the Nhat Hanh lecture at Loyola. “What I took away from it was the importance of contemplation and of becoming more mindful, compassionate and respectful in our political conversations.” She especially liked Nhat Hanh’s suggestion that Congress could become a sangha or community whose members listen deeply to one another rather than fight for their individual agendas. Naive? Idealistic? Maybe. But not to the 77-year-old monk who has been preaching this message for decades. “It’s so simple,” he said. “You can free yourself from the sorrows of the past and the fear of the future if you know how to hold onto the present moment. To me, the kingdom of God is available in the here and now. If God is available 24 hours a day, his kingdom is also available. The question is whether we are available to the kingdom.” Heidi Schlumpf writes from Chicago. National Catholic Reporter, September 12, 2003 |