|

Issue Date: September 19, 2003

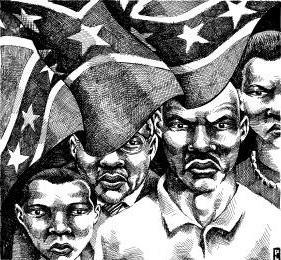

After decades of going north, many African-Americans are now returning to the South to find a region where much remains unchanged By DIANA L. HAYES Having lived in Georgia for more than 8 years, I often find myself wondering what century it is. Despite progress that has been made in Atlanta, “the city too busy to hate,” many areas of the state seem to dwell “in the Electric Mist with the Confederate Dead,” to quote author James Burke. Parts of Georgia and other Southern states live more than 150 years in the past, wishing for the return of the “good ol’ days” of the Southern aristocracy, when everyone knew their place and stayed in it. Georgia has recently made headlines for several less-than-glorious reasons. People called “flaggers” seek to reinstate the Confederate battle flag as the Georgia state flag. And a high school in Taylor County decided to hold a separate whites-only senior prom, as well as an integrated one. The school held its first integrated prom only last year. During the Great Migration (1920-1945), thousands of African-Americans left their positions as sharecroppers and domestics for the opportunity to be free of the “Jim Crow” laws that rendered them voiceless, voteless and poorly educated. They went to the North, the Midwest and the West. Racial discrimination still existed there, but they could vote, educate their children, own homes and have jobs that paid a living wage. Many young black people grew up hearing stories of the South from their elders or were sent “home” in the summers to stay with relatives. My sister and I first went to stay with our grandparents in St. Elmo, a small town outside Chattanooga, Tenn., at the ages of 8 and 7. My mother was expecting her fourth child, my youngest sister Cheryl. Our 3-year-old sister, Alice, stayed with my parents in Buffalo, N.Y. My father and my sister’s godmother drove us to Cincinnati. It was only years later that I learned why. The “Jim Crow” line started at the Ohio/Kentucky border, so in Cincinnati, “Jim Crow” (segregated) cars were attached to the back of the original line of cars from the North. My father feared we were too young to change trains and get on the right one. Cindy and I rode in a set of old, dirty, dark cars with hard benches. Every black person in those cars fed us, scolded us and looked after us like traveling royalty. As evening came, the porter brought fresh linen and made beds for us on the benches. We pulled into Chattanooga’s station the next morning, looking forward to a summer of swimming, playing with our cousins and going to church on Sundays and prayer meetings on Wednesday evenings. By the time we were in our teens, after many trips South, we began to feel uncomfortable about going “home.” We were used to the bustling city rather than the rural slowness of St. Elmo. And we had started to notice the differences. I remember my unease at the water fountains labeled “colored” and “white,” at the smelly lavatories reserved for “coloreds” and at having to wait in a shop until all of the whites were served. The Civil Rights Movement had begun, and my sister had joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. That last summer in the ’60s, our parents came early to pick us up because, as my grandmother reported, we “didn’t know how to act.” My older sister and I finally returned to the South under the encouragement of her daughter, who had gone to school and married in Atlanta. Atlanta, Charlotte and other cities are now choice destinations for hard-working, educated young blacks because the cost of living is lower, housing costs are significantly lower, and jobs are good. Cheryl was already here, and because of my arthritis I sought a warmer climate. We enjoy, most of the time, the slower pace, the wide-open green spaces and the friendly atmosphere. And yet, in many ways, the metropolitan enclave of Atlanta is an artificial jewel set in a predominantly rural state. I realize that much of the effort to “save” the battle flag, to hold separate proms and so on is a fearful reaction to the rapid changes taking place in the South. But many of the “flaggers” don’t seem to know their own history. Most of these people come from families that were never a part of the Southern aristocracy. After Reconstruction, they were farm workers and often sharecroppers. They had more in common with poor blacks than with wealthy whites, who often paid them to fight as substitutes in the Civil War. The simple truth is this: Seceding from the union was wrong, and the cause for which the Confederacy fought was wrong. Those of us in Georgia and throughout this country need to step firmly into the 21st century and lay the Confederate and Federal dead to rest. A separate but equal policy is unconstitutional, according to the Supreme Court of this land. The battle flag should not fly anywhere in the United States. It is an insult, not just to African-Americans but to all Americans. It is time to put the past behind us and move on, to tend to the needs of our nation, especially our nation’s children, and to allow racial and ethnic differences to serve as part of our colorful mosaic of life rather than as a basis for dislike and distrust. By now, we should all be too busy to hate. Diana L. Hayes is associate professor of theology at Georgetown University. National Catholic Reporter, September 19, 2003 |

Home to the South

Home to the South