Issue Date: October 10, 2003

Reviewed by RAYMOND A SCHROTH In the 1970s I regularly led an expedition of Fordham University students on a nine-hour trek from lower Manhattan’s Battery Park, up Broadway, pausing at universities, parks, squares and churches, up the long hill of the Harlems to the Cloisters, then up University Avenue and Fordham Road to the Bronx campus -- arriving in time for the Kentucky Derby on TV. Seventeen years later, after teaching or administering at four other universities, I returned and led “The Great Walk” again. But as we climbed the hill above 125th Street on the West Side, I had a sense that the world had changed. I was in Lima, Havana, San Juan. In 1983 Eric Sevareid, the CBS News commentator whose nightly “Evening News” analyses gave us a sense of what it meant to be an American, worried that unchecked immigration from Latin America was making the American Southwest the “dumping ground for all the region’s poor.” He worried that Spanish-English bilingualism would prove a greater strain on national unity than black-white biracialism. Language, he said, “is more fundamental than skin color.” Even if he got a little crusty after his 1977 retirement, Sevareid knew how essential a unified culture was to maintaining an American identity. He also knew that each new immigrant group faced unique problems in turning the e pluribus into the unum. Presuming that joining the unum was their goal. The four authors before us -- Richard Rodriguez, Linda Chavez, David R. Abalos and Demetria Martinez -- address, each from his or her own perspective, this crucial problem. Nor are they strangers to one another. Rodriguez blurbs Chavez’s book as a “remarkable American life.” Abalos cites Rodriguez and Martinez in his text. Martinez lauds Abalos for a “landmark work that will change forever the way we talk about machismo.” If Chavez has read the others she does not say. They write at a time when the influence of Hispanic-American intellectuals is more needed than ever, when, as any number of articles and studies show, the impact of this “minority” on the American character will soon be incalculable.

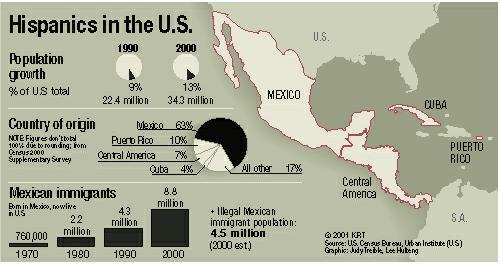

According to the census, Hispanics are now the nation’s largest minority -- “a turning point in the nation’s history,” says one scholar at the Pew Hispanic Center. Ironically, the emergence of the Latino “majority” has sent a buzz through academia where black and Latino academic programs compete for funding. After all, they ask, what’s “black” and what’s “Latino” when the races have been and are now intermarrying more than ever? Depending on whom you read, by 2050 from a quarter to a third of Americans will be Hispanics. Meanwhile, investigative journalists, particularly at Newsday and The New York Times, have documented how Latin American immigrant laborers, illegal and legal, are particularly vulnerable to contractors who hire them for dangerous jobs, at lower wages than competing workers. But Hispanics, Chicanos, Latinos -- the terms are used interchangeably in these books -- are vulnerable in more fundamental ways. The culture in which they grew up has become, depending on one’s point of view, the rock on which they might build a common identity or the drag that will isolate them from the American mainstream. In The Latino Male, David T. Abalos repeats familiar, grim statistics. The Latino jobless rate is 12 percent. Only 50 percent have a high school education, compared to 84 percent of the non-Latino white population. Only 10 percent have a bachelor’s degree. Latina young women represent 25 percent of high school dropouts nationwide; 24 percent of Latino families are headed by women, over half live near the poverty level. Their population, especially among Puerto Ricans, is ravaged by AIDS -- at a rate seven times higher than the non-Latino population. The Latino population represents a cluster time bomb of unemployment, AIDS, addicts and dropouts. These facts must be greeted with a gasp, a sense of urgency. Each of these books approaches this situation differently; and each author examines his or her own life in an attempt to give meaning to a larger demographic change.

Brown’s Richard Rodriguez, familiar as a commentator for National Public Radio and an occasional essayist on the PBS “Lehrer News Hour,” says he has never had an adversarial relationship with American culture. He thinks of the nation entire -- all Americans -- as “my people.” Subgroups are appropriate to argue for rights, but they must “merge with the whole, not remain separate.” He clusters his reflections around the color brown because, in terms of race relations, it allows him to cast so wide a net and haul in insights from every race and color dumped these days into the kitchen blender. As a writer he can identify with a black writer such as James Baldwin, but, as a sensible human being, he rejects the drum-drum of hip-hop music in his gym. Is it the “immoral lyric chugging along a rhythm track, only concerned with finding the rhyme for mutha#%&^*”? Rodriguez describes himself as a “queer Catholic Indian Spaniard at home in a temperate Chinese city in a fading blond state in a post-Protestant nation.” Yet Catholic readers will read him in vain hoping for much insight on how his Catholicism permeates his gay, Hispanic, American or TV essayist identities. The future is brown, he says, “as brown as the tarnished past.” “Brown people know there is nothing in the world -- no recipe, no water, no city, no motive, no lace, no locution, no candle, no corpse that does not -- I was going to say descend -- that does not ascend to brown. Brown might be making.” He might get away with this on TV with visuals compensating for the lingo, but reading it prompted one book critic to want to bop him on the head and say, “Get to the point.” A life lived in reaction In early February, Princeton University, as the Newark Star Ledger, put it, “pulled the plug” on an elite summer program for talented black college students from around the country who, they hoped, would pursue careers in public policy.

The pullout was a victory for the Virginia-based Center for Equal Opportunity, a mini-think tank that has hit up a series of universities, threatening lawsuits over their affirmative action programs. Their leader is the conservative Hispanic columnist who describes herself in her book, An Unlikely Conservative, as “the Most Hated Hispanic in America,” Linda Chavez. That bogus title is typical of the odd blend of victimhood and self-promotion that characterizes her tale of triumphs and woes. “I’d spent a lifetime being underestimated by others,” she tells us. “But I’d always proven myself.” If anyone bothered to “hate” her, it was not because she was Hispanic. Daughter of a handsome Mexican alcoholic father and a blonde, blue-eyed divorcee, Linda once thought of becoming a nun, but she lost interest in her religion and became a Jew to marry Chris Gersten, a socialist, a fellow Ph.D. student at the University of Colorado in Boulder. She was soured on affirmative action from the beginning. It pandered to ill-prepared Mexican students; and when, later at UCLA, she was assigned to teach them “Chicano literature,” her class rebelled and humiliated her. In Washington she got a job at the Democratic National Committee, then as a congressional aide -- jobs she knew she was not well-qualified for -- then at the National Education Association and American Federation of Teachers, then the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and back to American Federation of Teachers as an editor. A registered Democrat, she voted for Reagan in 1980 and was named director of the Civil Rights Commission. She registered Republican and got on the White House staff as a director of public liaison. She ran for the Senate from Maryland and lost badly to Barbara Mikulski. That she then described herself as a Catholic raised questions about the depth of her various conversions. Her “hated” phase came with her job at the U.S. English Foundation, which opposed bilingual education. In insisting that American Hispanics learn English, it seems to me, she was on firm ground, but it took her 14 months to discover that the group’s founder was a racist kook obsessed with the high birth rates of immigrants. Most Americans would have never heard of Linda Chavez had not George W. Bush nominated her for secretary of labor and had she not, out of ambition, covered up her having had in her home an illegal Guatemalan immigrant woman for two years in the early 1990s. It’s hard to feel sorry for her. If she would read her own book through another’s eyes, she might glimpse the irony of her resume: Opposition to affirmative action -- not blood or religion or party or some clear system of beliefs -- has been the driving force of her career, a series of jobs where she gained entree, preference, because of her Spanish last name. Saved from patriarchy

David T. Abalos, a religious studies and sociology professor at Seton Hall University, whose father came from Mexico in the 1920s, is a victim too, but, as he tells us in The Latino Male, not of political enemies but of the Latino culture that raised him, “an abused child,” with crippling notions of sex, religion, and particularly the respective roles of men and women in their intimate relationships. His book is a conversion story, a tract proposing a formula for the transformation of his fellow Latino men from abusive patriarchal sexists into mature men of good will. As a gang member in Detroit, young David once grabbed a white boy and smashed him in the face, just to prove he was tough. When the boy fell down in tears, David felt not tough but sick. He sensed something wrong with his way of life. His Chicano/Mexican tradition gave him permission to dominate women. His Catholic training reinforced patriarchy, but told him to transcend his body, to put women on pedestals. Hispanic males are, he says, a volatile bundle of contradictory passions -- part Spanish bullfighter/soldier in their sexual exploitation, part Indians, victims of the blue-eyed American males. To resolve the tension they turn to drink, drugs, violence, and womanizing. Abalos joined the seminary to escape his sexuality. He left and married, but became distant from his wife. But gradually his wife’s love, his brother who died of AIDS, and colleagues helped him devise a therapeutic system based on Jungian psychology to move parental love from dominance to nurture. It is odd, though, that Abalos is so negative toward the church and toward “assimilation,” which he considers a surrender to capitalism. I would think a good American Catholic college education might both nurture Latin youths and work them into the larger society. According to Mireya Navarro (The New York Times, Feb. 10), Latino students face extra obstacles on the way to an education. Only 16 percent of Latino high school graduates earn a college degree by the age of 29. Attached to their extended families, they stay home during their college years and get jobs, go to community colleges with flexible schedules, don’t commit themselves to their studies and drop out. As an assistant dean and professor I have met Latino students who have been here more than six years and don’t speak English well enough to take part in a class discussion. Now I know why. A poetry of longing Of these four books, Demetria Martinez’s collection of poems rewards reading again and again -- partly because all real poetry demands another reading. If Richard Rodriguez’s line of thought sometimes slips away in the wind like a kite freed by a broken string, Martinez will hit us with images that are stronger -- “we boil the roots of telephone cords torn from the black soils of sleep” -- than they are clear.

Reading poetry it is often harder to draw conclusions about the interaction between the poet’s life and her ethnic identity. For “confessional” poets, the scenes spring immediately from personal experience, yet poets speak through many voices, their spirits temporarily inhabit the bodies of alien subjects. In “Breathing Between the Lines” (1997) she writes vividly of longing, of separation from friends or lovers -- particularly a Vietnamese -- of Albuquerque memories, of tension between the Spanish and English languages, and how each either helps us to hide or to reveal who we really are. Perhaps because in 1988 the U.S. government, prosecuting her for helping to smuggle in two Salvadoran women, tried to use her poetry in court, her strongest poems are political. In her recent collection, The Devil’s Workshop, the tension between the two cultures has, for the most part, faded into the background; she focuses more on illusive scratches on her heart. The standard poet’s tools -- rhyme, metrical pattern, music -- stay locked in the toolbox. Each piece is a brief, spare string of metaphors -- some familiar, “... catch lightning in a jar,” others startlingly apt, like death as a dishwasher who has dried her hands on her apron and “steps out on the porch to call/My parents in … ” The dominant voice, a woman in her late 30s, is not always a happy one. Her muse, a lover, once drove her pen “like a tanker into the rocks,” but saved her from the writer’s curse of silence. He is gone. Planes take off, separating lovers -- or fleeing them. A man has flown her “like a kite.” A drug addict defies those who would restore “some semblance of/Original beauty.” An abused woman grabs her children and a suitcase and flees her husband in Managua. Are these the women in Abalos’ study, the cost of the machismo embedded in Latino culture? One of the best poems, “Upon Waking,” depicts a dream inspired by the death of Amadou Diallo, shot 41 times by panicking New York police in 1999. Helicopter gunships blast away at dark-skinned people trapped against boulders on an island. “I cried out at a wall of wind:/‘No, stop, they have histories’ -- but it was too late.” Another blunt, political piece warns “the sisters,” “colored folk,” of the exploitive “white man,” who “lowers himself into you, primitive, savage beauty,” when he can “come. And go.” She weakens it, I think, by finding a rhyme for “tuck.” In recent years any number of black-brown social commentators -- Randall Kennedy, Stanley Crouch and others, plus an article by Gregory Rodriguez in the Atlantic Monthly (January/February 2003) -- have told us that the racial future is in a “Mongrel America.” It is significant that Texas and California, the two states soon to have a Mexican-American majority, were quick to abolish affirmative action. They are in a position, says Gregory Rodriguez, to “claim their brownness -- their mixture. This is the harbinger of America’s future.” I’ll have to write about this again 10 years from now, when we take the “Great Walk” again. Jesuit Fr. Raymond A. Schroth is the Jesuit Community Professor of the Humanities at St. Peter’s College. His email address is raymondschroth@aol.com. National Catholic Reporter, October 10, 2003 |