Issue Date: October 10, 2003

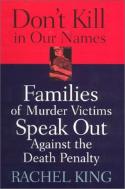

Reviewed by CHRIS BYRD Alaska doesn’t have the death penalty. A legislative initiative to reinstate it failed in 1996. Many of the legislators who voted against reinstatement rejected it after hearing Marietta Jaeger tell her story. During a 1973 family vacation, Jaeger’s 7-year-old daughter, Susie, was kidnapped and murdered. Yet Jaeger came to forgive the killer and work to abolish capital punishment. She’s one of the remarkably courageous persons profiled in Rachel King’s book, Don’t Kill in Our Names. A veteran abolitionist, King helped lead the campaign that turned back the death penalty in Alaska. She currently works as a legislative counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union. This is her first book. All profiled are members of Murder Victims Families for Reconciliation, a national group of people who have lost family members to murder yet oppose capital punishment. It’s an exclusive club; as the author notes, no one wants to join. These persons’ narratives upend readers’ assumptions about murder victims’ families and the nature of forgiveness, notably that murder victims’ families’ understandable grief and rage won’t allow them to forgive and they justifiably desire capital punishment to gain some measure of closure. A former nun, Maria Hines forgave Dennis Eaton, who killed her brother, Virginia state trooper Jerry Hines, and later became one of Eaton’s spiritual advisers who accompanied him to his execution. She addresses closure’s illusion from a Families for Reconciliation perspective: “To say, however, that vengeance and closure can exist together is a contradiction in terms because the other side of the coin of vengeance is anger and as long as we hold onto anger, our grieving isn’t over.” It wasn’t easy, however, for members of the group to learn to forgive the people who killed persons they loved. SueZann Bosler survived multiple stab wounds to her head and underwent surgeries and a long painful rehabilitation period before forgiving James Bernard Campbell, who murdered her father, the Rev. Billy Bosler. Campbell killed Billy Bosler in the same attack as the one on SueZann. Another member of the group, Ron Carlson, felt as if his life was unraveling after Karla Faye Tucker murdered his sister, Debbie Thornton. “My days,” he said, “were pretty much all the same. I’d get up in the morning and start my day with a joint. I’d go to work high and stay high. I’d drink and smoke pot during lunch, and as soon as I left work I was smoking another joint and drinking more beer.” Their own anger was the greatest obstacle members had to overcome before they could forgive the people who killed their family members. Carlson said, “I wanted to take that same pickax and leave it in the heart of Karla Faye Tucker.” For him and others, a religious experience turned their hearts away from revenge. At the time his grandmother, Ruth Pelke, was murdered, Bill Pelke worked as a crane operator for a steel company in Gary, Ind. One night, desperate to get his life under control after it had started to unravel after the murder, Bill began to sob. He then recalled his grandmother’s deep Christian faith and example and let her spirit guide him as he prayed. Bill became convinced Ruth wanted him to show love and compassion toward Paula Cooper, the juvenile who killed the grandmother. After his young son, Tariq Khamisa, was murdered, Azim Khamisa was motivated to start a foundation to prevent youth violence. Cofounders were Tony Hicks, the juvenile who killed Khamisa’s son, and Hicks’ grandfather, Ples Felix. A devout Muslim, Azim acted on a spiritual counselor’s advice: “Compassionate acts undertaken in the name of the departed are spiritual currency, which will transfer to Tariq’s soul and help speed his journey.” For the most part, King judiciously allows these extraordinary persons to speak for themselves, but her inexperience as a writer is sometimes evident. She writes in the introduction that readers cannot help but be moved by these stories. That’s a premature judgment best left to the reader. Her summary, moreover, falls flat. In a book about others, references to her own struggles with forgiveness are curious and off-putting. King also fails to explain several key developments in the narratives fully. For instance, she touches upon but doesn’t probe SueZann Bosler’s apparent yet problematic romantic relationship with the district attorney prosecuting her father’s murderer. King furthermore doesn’t help readers understand terms used by Khamisa’s Muslim sect. There’s a more significant flaw with the text, however. In the last two chapters, King shifts her focus from opposing the death penalty to restorative justice. She rightly believes this form of justice that encourages victim-offender mediation holds offenders more accountable and offers victims more opportunities for healing. Even other dedicated abolitionists will take exception, however, when King argues long-term imprisonment isn’t a solution to violence. Where the death penalty is concerned, life without the possibility of parole and mandatory sentences of at least 25 years are viable and meaningful alternatives to capital punishment that will hold murderers accountable and keep society safe. Don’t Kill in Our Names doesn’t have the impact it should. Perhaps a more seasoned writer would have written a more satisfying book. Nonetheless, King’s willingness to bear witness to these exceptional lives is commendable. There’s enough in these stories to instruct hearts and change minds. Chris Byrd writes from Washington, where he is a veteran of the movement to abolish the death penalty. National Catholic Reporter, October 10, 2003 |