Issue Date: October 17, 2003

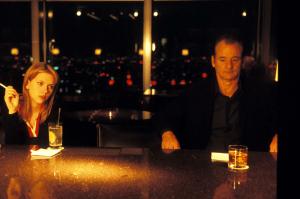

In translation or otherwise By JOSEPH CUNNEEN Sofia Coppola knew from the start what she was doing in Lost in Translation because she wrote the scenario with Bill Murray in mind to play the lead. Murray should get an Academy Award nomination for his work as Bob Harris, a disillusioned, fading movie star, in Tokyo to do a whiskey commercial. Suffering from jet lag, forced to field idiotic phone calls from a wife back in the United States interested only in redecorating their house, he is deeply depressed by the combination of fawning attention from the advertiser’s underlings and wildly pretentious demands (in Japanese) by the commercial’s director. Murray is both sad and funny, going from physical farce to ironic self-reflection. Unable to sleep, he spends too much time in the bar of the Park Hyatt hotel, where he makes the acquaintance of Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson), a much younger -- Johansson in fact is only 18 -- but equally dislocated American, whose ambitious new husband has left her behind to do a photography job elsewhere in Japan. Coppola brilliantly suggests a mood of dislocation by placing these two thoughtful people in a noisy and garishly lit world of Tokyo nightlife, brilliantly captured in Lance Acord’s photography. She suggests an instant affinity between the two displaced Americans, makes good use of silence to allow us to read the thoughts suggested on their faces, and keeps emotions subtle and muted. The central story never collapses into sentimentalism, and there are hilarious sequences: In one, Murray battles an aggressive call girl; in another, he appears in a wonderfully inane Tokyo TV talk show. Funniest of all is the scene in which Harris makes his whiskey commercials for a hyper-excited director who demands greater intensity in his delivery and a conciliatory interpreter reduces the tirade to two or three words. Music supports the languorous mood of the central relationship, conveying the understanding that this encounter between a disillusioned older man and a confused, lonely young woman is intimate without being primarily sexual. The deep emotional needs of Harris and Charlotte give emphasis to the artificiality of the small slice of Tokyo they encounter. But although they are too immersed in their own melancholy to make contact with everyday Japanese life, they manage to help each other through a lonely period. Each is moved when the other sings karaoke, and there is a touching moment when Harris carries the sleeping Charlotte to her hotel room and tucks her in. Some may complain that Coppola’s script is undeveloped, but she successfully draws on the emotions of the audience. She simply refuses to tie up her narrative, distilling an intense experience with consummate skill. French documentary filmmaker Nicolas Philibert shows equal mastery while bringing us into the day-to-day life of a French village school in To Be and to Have (“Être et avoir”). The teacher, Georges Lopez, working with a small class (12 to 15) age 3 and a half to 11, will make audiences wish they were back in school. He is demanding, but attentive to each child, an artist who builds community and heals quarrels. Philibert stayed with the class for seven months and makes good photographic use of the changing seasons in the Auvergne region. The children obviously became accustomed to the director’s camera, and moments of hilarity and deep emotion develop with complete spontaneity. Philibert doesn’t pry into Lopez’s life outside the classroom. All we know is that after more than 20 years of teaching, he is about to retire. Only a few brief scenes are shot in the homes of the students, showing the difficulty parents often have in helping children with their homework. Lopez thought that the range of ages among his pupils was an advantage. When the teacher is focusing on one group, the rest learn to work on their own. “They quickly become independent,” he says, “responsible for themselves and sometimes for others.” The film often shows Lopez dealing with students one-on-one, but he also supervises the comments of the class on penmanship. Evaluations of renderings of “Maman” ranged from “It’s a little bit good” to “It’s lots of good.” Although there is no developing drama, it’s hard not to become deeply involved in “To Be and to Have.” The children are attractive, but the movie makes clear they are sometimes resistant or hard to reach. When Lopez takes one girl aside near the end -- she is to move on to intermediate school but still has a serious problem in communication -- we have a convincing example of the teacher’s tact and deep empathy. He asks her if he is right in mentioning her difficulty in his report to her new school. “You’ll be busy all week in your new school,” he tells her, “but perhaps you will come to see me on Saturday and we can talk over your progress.” It is clear that Lopez’s success does not come from some revolutionary new teaching method. In fact, he is a French traditionalist who gives his students regular dictation. This makes the rapport between him and his students all the more convincing when he says goodbye to them after the last class. He is retiring and it is clear he will miss these children, and they will remember their teacher long after the children have forgotten their arithmetic. Joseph Cunneen is NCR’s regular movie reviewer. He can be reached by e-mail at scunn24219@aol.com.

National Catholic Reporter, October 17, 2003 |