Issue Date: December 12, 2003

As scientific discoveries unveil delicate balance of 'coincidences' that made evolution of life possible, the question of Creator is raised anew By RICH HEFFERN Science, once seen as the enemy of spirituality, is now making common cause with it in one area, in a search for meaning and purpose. It seems absurd to think of humans influencing distant stars, but science tells us now that the simple fact of our existence does turn out to have profound implications for the ultimate questions. According to a growing number of hard-nosed physicists, the laws of nature are so finely tuned, and so many “coincidences” have occurred to allow for the possibility of life, the universe must have come into existence through intentional planning and intelligence. Twenty or 30 years ago, science had closed the door on spiritual speculation. The divine was seen as wishful projection, existence as only an interaction between chance and necessity, and human behavior as inexorably determined by fixed variables. That has all changed in recent years. Charles Townes, the Nobel-winning co-inventor of the laser, said two years ago that the discoveries of physics “seem to reflect intelligence at work in natural law.” And Francis Collins, director of the Human Genome Research Institute, declared: “A lot of scientists really don’t know what they are missing by not exploring their spiritual feelings.” This sea change results from a number of factors, including breathtaking discoveries in quantum physics, psychology and biology. A major influence has been scientific speculation about what is called the Anthropic Cosmological Principle, a summary of observations from the ongoing effort to solve the puzzles of the universe. The cosmic fine-tuning described by the Anthropic Principle works something like this: Mornings we all get out of bed, and it’s a matter of putting your feet on the floor then standing up. Yet the prerequisites for this act are complex, including parents and a line of ancestors stretching back. An ultimate condition is the existence of sentient life in the universe. We know of at least one instance -- us. We also know, thanks to 20th-century scientific discoveries, that the development of sentient life depends on a complex sequence of events. Stars and then planets must have formed, then those first generation stars made of simple elements like hydrogen and helium must have forged in their fiery furnaces more complex elements like carbon, zinc and iron. Then those stars needed to age and explode, thereby releasing those complex elements to be folded into the mix that formed second- and third-generation stars like our sun. Planets heavy in those elements must have also developed, where biological evolution can take place. This is our story: We are literally made of fossilized stars. We used to think that we humans were at the center of the universe. The light-giving sun and stars circled around us -- or so it seemed -- so obviously we were important, living at the center of things. Copernicus’ discovery in the 16th century that, counter to appearances, the earth rotated while circling the sun began a revolution that gradually but inexorably dethroned humanity as the center of the universe. The idea we were specially created yielded to evolution’s explanation. It sank in gradually, with one new scientific discovery after another, that we’re not privileged characters, just inhabitants of a garden-variety planet circling a run-of-the-mill sun in our galaxy’s backwater, sentient and aware but certainly not at the center of things. Surprisingly, this view has yielded in turn recently. In delicate balance Many scientists suggest now that all the basic characteristics of the observable universe -- the strength of its main forces like gravity, the masses of its particles, the rest mass of its electrons -- are in a delicate balance that has allowed for the development and evolution over time of life, folks like us, who get out of bed mornings, think and contemplate the world around us. For example, the value of the gravitational “constant” tells us the strength of gravity, the force that keeps us from floating off into the sky. This is an actual observed mathematical quality of gravity, similar to pi as a measure of the circumference of a circle. It’s hard-core science fact, as reliable as the chemical formula for producing glue or plastics. If the gravitational constant were infinitesimally different one way or the other, the force of gravity would be much lesser or much greater, with bad consequences for the evolution of stars and planets. Greater gravity would have prevented cosmic expansion and the formation of stars, putting a halt to life’s evolution. A lesser force would have dissipated the energy from the initial formation of the universe. Planets and stars could not have developed. If gravity were slightly different, we simply would not be here asking questions about it or trying to overcome that gravity every time we take off in a plane. Instead, it happens that the force of gravity is just right. Physics shows that all the basic phenomena of nature and the laws that govern them have particular constants or ratios associated with them -- the gravitational constant, the electric charge, the mass of the electron, Planck’s constant from quantum mechanics, and others. The actual mathematical values of these constants and ratios are arbitrary. The laws would still operate if the constants and ratios had other numbers, yet the resulting interactions between them would be radically different, and the final outcome would be a different universe, probably minus its sentient life. The evolution of life, in other words, is extremely sensitive to the values of physical constants and ratios. Varying the values by small degrees would have prevented life. The fact that the universe emerged in the Big Bang some 15 billion years ago with just the right values for these constants to enable life formation seems remarkably like fine-tuning for a purpose, in order that life could evolve. There are a large number of “coincidences” inherent in the fundamental laws of nature. Every one of these coincidences or specific relationships between fundamental physical parameters is needed, or the evolution of life and consciousness as we know it could not have happened. The collection of these coincidences is an undisputed fact, and collectively they have come to be known as the Anthropic Principle.

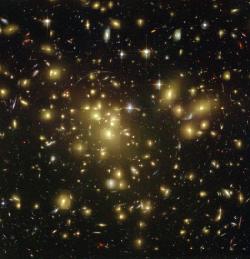

“The sudden appearance of the correct biocentric parameters ‘out of nothing’ is essentially tantamount to a miracle,” writes Michael Corey, author of The God Hypothesis: Discovering Design in Our “Just Right” Goldilocks Universe, “because there is evidently no other way to account for this perfect life-giving format by random processes alone.” Michael Turner, astrophysicist at the University of Chicago Fermi Lab, puts it another way: “The precision is as if one could throw a dart across the entire universe and hit a bull’s-eye one millimeter in diameter on the other side.” Why it is this way Scientists point out that this delicate balance extends to all of nature’s fundamental constants simultaneously since they all interact with one another, directly or indirectly, in a wide variety of ways. The least statement of this fact is called the Weak Anthropic Principle, and essentially states that since we are here, the universe must have the properties, or coincidences, so that we could evolve. Although unquestioned, the Weak Anthropic Principle offers no insight as to why the universe is this way. Some, based on their interpretation of quantum physics, see a predominant role for the observer, and have gone so far as to suggest that observers are needed to bring the universe into existence. This version is called the Participatory Anthropic Principle. Of course, the universe got along just fine before we came to exist, and also does so in areas where we can’t make any observations. Others have gone on to postulate the Strong Anthropic Principle, which states that in order for the universe to exist at all, it is somehow necessary for it to have these special properties. In other words, the universe must have been “constructed” this way, and could not have come into existence any other way. The Final Anthropic Principle goes a step beyond the Strong Anthropic Principle and says that not only must life come into existence, but once it does, it will last forever. There are many interpretations of what these degrees of the Anthropic Principle mean. Some say that the Principle, especially the Weak Anthropic Principle, is a tautology, and essentially meaningless. At the other end of the spectrum are those who say that the anthropic observations clearly demonstrate the presence of divine intelligence before the beginning of things, tweaking the numbers so we would wind up in the world. Instead of introducing the God concept to explain the precision tuning, many scientists propose that there exist countless “universes,” vast systems independent of one another. Force strengths, particle masses, expansion speeds and so on vary from universe to universe. Due to varying values, many of these universes erupt into existence, then wink out in a few seconds. Others may be just huge cosmic empty spaces. Sooner or later, in one of these universes conditions will be just right to permit life to evolve. Obviously only such a “somewhere” could be observed by living beings with senses to take in the world around them. It’s a kind of “shotgun” approach to creation: Eventually, the right parameters will happen by chance, given an infinite number to work with. Martin Rees, the British astronomer royal, proposes that our universe is part of a greater collective, a “multiverse” in which most of the other rooms are empty. He envisions a grand ensemble of universes, in some of which the laws allow for an even richer development of life than in our own. What are the alternatives to this multiple-universe theory? The principle alternative is that there exists just one universe. Its force strengths and particle masses are the same everywhere. And these values were selected with a view to making life possible. They were chosen by a Mind or a Creative Principle that can reasonably be called “God.” Other scientists are cautious about drawing any conclusions about anthropic matters, suggesting that the delicate balance of values might be an inevitable consequence of a deep natural structure yet to be revealed, possibly an artifact produced by “superstrings,” an abstruse explanation. “If that’s the case, then the Anthropic Principle will at best have been a red herring when it comes to understanding gravity,” says science writer Timothy Ferris. Nothing stirs more controversy now in science than the Anthropic Principle. Some say it’s just a new version of the old argument for the existence of God from design. A watch found on a beach implies a watchmaker. The complexity we observe in the universe implies a designer. In thinking through the implications, it appears there is also no requirement that the life be human, or even carbon based. “A universe capable of humans does not mean to suggest that humans were implied from the start. Rather it is some sort of beings of our general complexity that are intended, capable of being consciously aware of themselves,” says John Polkinghorne, last year’s Templeton Prize winner, a physicist who became an Anglican priest. Physicist Paul Davies writes: “We have to be very careful here. This term, the Anthropic Principle, is a misnomer. In 1974, British physicist Brandon Carter coined the term and [later] said he deeply regretted it. It implies that somehow the universe has been created for the benefit of Homo sapiens, which is absurd. We’re actually talking about the existence of life itself, of carbon-based organisms. It’s really a bio-friendly principle, not an anthropic principle.” Polkinghorne believes the Anthropic Principle is a monkey wrench thrown into the contemporary science world: “The Anthropic Principle came as a great surprise to dwellers in science-land. They prefer to talk in as general terms as possible and so their natural instinct was to suppose that our universe was nothing very special among possible worlds. They had not at all anticipated that there would be something of unique significance in the precise form taken by our laws of nature. “The more one thinks about the plot of life, the more that plot thickens.” Polkinghorne points out that we should not feel upset when we realize the universe in which we live is immensely big, containing 100 billion galaxies each with 100 billion stars. We feel like a tiny speck of dust compared to the vast vaults surrounding us. “If all those trillions of stars were not there, we would not be here to be upset about them. Only a universe as big as ours could last the 15 billion years it takes to make women and men.” Even the gigantic size of the universe is an anthropic necessity. God of the gaps As science has pushed back the veil from the workings of nature, religion has typically invoked God to explain the gaps in our knowledge.

Yet Charles Darwin gave us the possibility of an alternative explanation. “We have come to expect,” says Polkinghorne, “that scientifically posable questions will receive scientifically stateable answers, however difficult those answers may sometimes be to find. No one should shed a tear about this since the God of the gaps was only a pseudo-deity anyway. He faded away with every advance of knowledge, like a kind of divine Cheshire cat.” Polkinghorne suggests that God is involved with creation in its entirety, not just the bits that are difficult to explain. Theology’s job is to stand side by side with science, offering its own insights as humans continue to push back the frontiers of the unknown. He writes: “If this underlying physical foundation for the natural order did not gradually evolve by the process of natural selection into its present format, if indeed this foundation of life-supporting laws and constants emerged out of the Big Bang, perfectly fine-tuned and ready for action, then it means that some other explanation besides Darwinian evolution has to be found for the perfect setup of nature’s fundamental constants. The anthropic principles describe a universe whose origins and purpose are still veiled in mystery, but one that seems to favor life, beauty and contemplation. Some feel that we have only just begun to plumb the depths of that mystery. Dominican Fr. Cletus Wessels, author of Jesus in the New Universe Story, told NCR: “In light of these recent discoveries, some might say the emergence of human life is the primary goal of the universe story. But we humans have emerged late, much has gone on before we arrived, and certainly the story has not ended with us. It goes on into an unknown future, perhaps for billions of years. “Even to say that the coming of Jesus is the ultimate goal is a shortsighted vision of the story. The life, death and resurrection of Jesus had a powerful impact on Western culture and the Christian community, but the God of the universe story unfolds within the vastness of the unknown future in ways beyond our comprehension. What is essential is to recognize the intimate, loving presence of God unfolding from within the whole universe.” There is a real point of convergence between science and spirituality. Each is telling us something about the miraculousness of our existence. Rich Heffern is former editor of Praying magazine. His e-mail address is heffern@diocesekcsj.org.

National Catholic Reporter, December 12, 2003 |