Issue Date: December 12, 2003

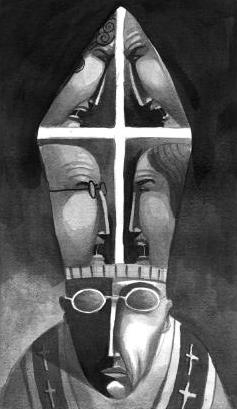

Assessing the ordination of Gene Robinson and responses to it By RICHARD THIEME Just as California is often said to be the leading edge of American popular culture so that what shows up there will soon show up in Pittsburgh, the Episcopal church often serves as a bellwether for Catholic and Protestant churches as to what to expect in coming years. Not surprisingly, the issues being discussed today are sexual. Above all, they are homosexual, thanks to the consecration of a gay man who lives openly with his lover as the Episcopal bishop of New Hampshire and the recent decision by the Massachusetts Supreme Court that the state’s ban on gay marriage is unconstitutional. Carl Jung said that when we talk about religion we are really talking about sexuality and when we talk about sexuality we are really talking about religion. Jung was speaking, of course, in the context of Western notions of identity, sexuality and autonomy, a context most Americans share so unthinkingly that we don’t pause to consider that an Asian or African bishop who expresses distress over homosexuality in the church may be standing on an entirely different platform. Cultural differences do make the conversation about sexuality more complex, but from the perspective of Western culture alone, there are issues enough to stimulate reflection on why, when the Rev. V. Gene Robinson was consecrated a bishop of the Anglican communion, distress flares went up all over the communion, even though those flares did not all signal the same sources of distress. First, let’s consider the broader question of sexuality in the church. Whenever we discuss human sexuality in an ecclesiastical context, issues are distorted as surely as our images are warped by the curves of a funhouse mirror. Sexuality is always charged with emotion, but the passionate intensity caused by linking sexuality to what we believe are God’s sexual preferences seems to release a particularly nasty kind of ranting and judgmentalism. As Jung said, the lines between sexuality and spirituality are murky. Our religious rituals are suffused with the language of sexuality. We speak of love, we speak of being close and caring, we speak of being touched; we speak of surrender, losing ourselves in God and one another, and we speak of being one body, one flesh, one extended if imprecisely defined and often dysfunctional family. The language of mystical ecstasy is the language of the lover. It speaks of union beyond simple intimacy, of being penetrated with joy and abandon. Who has not noticed, during a charismatic prayer service, the beatific smiles on the faces of our brothers and sisters, rapt in adoration, their hands raised in what can only be described as delicious sensual rapture? With the Anglican poet and pastor John Donne, we beseech our God to batter our hearts because we will never be chaste unless we have been ravished, never whole until we have been consumed. The pervasiveness of sexuality in religious experience helps us understand the widespread terror of sex found frequently in the church. The inability to discuss sexuality clearly, simply or directly is caused by that force field of distortion and self-deception. We may begin the discussion in a civil tone, but sooner or later we find our voices rising and our feet socketed in muck. The waters muddy and the going gets slow. The demands of honesty Stating the simple truths of our lives, often an easier task in non-ecclesiastical contexts, is considered heroic when done in the context of the church. Normal people saying normal things about their normal lives are turned into saints or devils because their honesty is so anomalous. So when an Episcopal priest who lives openly with his gay partner in a committed relationship is consecrated a bishop in the Anglican communion, it is to be expected that the event will be treated as a major crisis. Men who are only being themselves and disclosing who they have always been are described as the worst kinds of subversives, undermining the Gospel and the sanctity of the church. When I was preparing for the Episcopal priesthood, I noticed that one of the intentions of a long period of training was to socialize us to accept the fact that when we performed liturgical functions we would be the only men in the church wearing what looked like dresses. That socialization process stands as a metaphor for how sexuality is cloaked and hidden inside the black cassocks, neutralizing our bodies in generously draping folds. Who knows how many gay men and lesbian women hide inside those cassocks? Who knows what others really do in the privacy of their lives? I can only say that when I was in seminary it looked as if about one-quarter of the students preparing for the Episcopal priesthood then were gay. Sixteen years in the ordained ministry suggested that this was a reasonable estimate. It is from those clergy that bishops are chosen, so naturally there are plenty of gay bishops. Many of them share this fact in confidential conversations but are reluctant to broadcast it to the world because they have been taught that the real sin lies not in the being or the doing, but in the saying what is so. A church coming out of the closet The first bishop under whom I served, Otis Charles, was a married man with five children who after several decades of marriage announced that he was a gay man who had lived a lie. Then dean of the Episcopal Theological Seminary in Cambridge, Mass., he divorced and moved to San Francisco where he continues to exercise a number of compassionate ministries. “The real issue is that the church is coming out of the closet,” he said. “That’s the fact. Both the clergy and the episcopate have large numbers of gay men and lesbians. And the worst part is, in the U.K. and the U.S.A. there was a high degree of tolerance as long as you did not speak. The most severe criticism I received in general [when I came out] was, Why do you need to talk about it? Be what you want, just don’t make us acknowledge it.” Charles believes that sanctioning such dishonesty impairs the health and well-being of all in the church. “We have excluded a large area of sexuality by not talking about it and this has a huge negative impact not only on individuals but also on the community, on the church. How can a bishop be in relationship with members of that community if there’s a whole area of their lives that cannot be discussed?” I once served an urban parish the members of which spoke in glowing terms of two previous rectors with long tenures. They described them as “celibate men” who lived chastely with “companions.” The congregation’s commitment to denial was bone-deep and baffling when it was obvious to me that these men were living with gay lovers. “You need to understand that there is a yuck factor,” said a parish priest about the reactions of some church members to Robinson’s consecration. “As long as they don’t have to think about what it means, they can live with the abstraction. They often agree that the consecration merely ratified what everybody has long known to be true, but when they visualize what it means to have gay sex, many straight men and women blanch.” Perhaps they feel similarly about the blessing of same-sex unions (which is practiced in several dioceses but not sanctioned by the church as a whole). In that discussion too we hear the same theological and scriptural rationales for positions on all sides of the conversation, but those stated positions frequently obscure the fact that people are not talking about religion so much as sex and how they really feel about homosexual sex. Anyone who followed the path of women to ordination as priests and bishops in the Episcopal church can write the script as to who is saying what on which sides of the question and what they are saying. When a sexual controversy erupts, it is like calling central casting and asked them to send over the usual suspects. So I will merely invoke rather than describe their predictable positions. You, dear reader, can fill in the blanks. The consecration raises thorny legal issues for the Episcopal church that are just beginning to be discussed. Some American dioceses are threatening to withdraw from the Episcopal church over this issue and some want to establish alternative structures of authority based on theological similarities rather than tradition, hierarchy or geography. This constitutes a novel challenge for the church. When women’s ordination posed a similar threat to political unity a few decades ago, some parishes left the church but had to leave behind the parish’s buildings and belongings because they were owned by the diocese. This time, the threat of whole dioceses to withdraw raises the question of whether parishes wishing to remain faithful to the larger body would have to surrender their property to the conservatives and head for the nearest high school auditorium to worship. This question is currently being studied by canon lawyers, and no one knows how it will be resolved. But this, as I said, is from the Western point of view. When we listen to some of the Asian or African bishops who are distressed, we find they are not concerned primarily with the issues as touched upon above because in their cultures, identity, community and human sexuality are framed so differently. The prism of culture Archbishop Peter Akinola of Nigeria, speaking “for and on behalf of the working committee for the Primates of the Global South,” tells us they were all “appalled” that the Episcopal Church USA (ECUSA) “ignored the heartfelt plea of the communion not to proceed with the scheduled consecration” of Robinson and the “clear and strong warning of its detrimental consequences on the unity of the communion.” He continues, “We can no longer claim to be in the same communion. We cannot go to them and they cannot come to us. We will not share Communion. We have come to the end of the road.” That might sound like a homophobic American voice, but Akinola and his African colleagues do not see it that way. To them, the consecration “clearly demonstrates that authorities within ECUSA consider their cultural-based agenda of far greater importance than obedience to the Word of God, the integrity of the one mission of God ... and the spiritual welfare and unity of the worldwide Anglican Communion.” Persons who claim to speak from a position that transcends “cultural-based agendas” are usually signaling their own cultural-based agendas. A similar stance was taken by Archbishop Benjamin Nzimbi of the Anglican Church of Kenya who announced that his church will have nothing to do with Robinson or any of the 53 bishops who participated in his consecration. He declared that they are no longer Anglicans and that “we cannot be in the same communion with Robinson, his diocese and the bishops who were in the consecration,” adding that the devil has entered the church and God cannot be mocked. What cultural contexts might help us understand these pronouncements? Willis Jenkins, currently a fellow of the Institute for Practical Ethics and Public Life at the University of Virginia and a doctoral student in environmental ethics and religious studies, lived in 1998 in rural Uganda, where he taught in a seminary for the Anglican Church of Uganda. Because he lived in a village where homosexuality was becoming an increasingly familiar issue, he observed both the popular and the Episcopal reaction to it. “I was taken aback by the intransigence of the discord” between progressive and conservative elements of the church, Jenkins said. He became frustrated with what seemed to him to be the rhetoric of ethnocentrism. “Much of the tension,” he concluded, “is rooted in cultural values,” and the debate does not so much need theological or hermeneutical attention as it does “recognition of mutual ethnocentrism.” Both Ugandan and American bishops are guilty of ethnocentrism, Jenkins believes, and both, perceiving their own cultural categories to be universal, create the ground of fear on which they stand. Jenkins distinguishes numerous reasons for this dynamic, including a long history of imperial dominance in Africa. Rural bishops resist the perceived allegiance of the urban dioceses to Western influences and sources of funding. But equally critical are fundamental issues of identity. The core value of the villages of southern Uganda is social participation, which creates a community cohesion needed for agricultural subsistence. Each person has a prescribed role and the sign of adulthood is the ability to provide children. Identity is thus determined by family position, and social role is determined by identity. Neither identity nor social role is fluid. So the encroachment of Western notions of individual identity and sexual promiscuity of any kind are subversive of the very fabric of society and an affront to the theological underpinnings with which they are fused. It was impossible for the people with whom Jenkins lived to conceive of a homosexual as an individual whose sexual expression is a function of his or her core identity. Such categories were literally unthinkable. Heterosexuals for the same reason simply do not exist. Jenkins speaks from a point of view determined by his experience in a southern Ugandan village. But to speak of African bishops or an African perspective on sexual issues is to falsify through homogenization a complex continent characterized by many diverse cultures. Charles recalled a Nigerian student at the Episcopal Theological Seminary who was asked to speak to his cohorts about Africa. The student said he would try, but that he had never been outside Nigeria until he came to Boston. Charles speaks of these cultural issues in a very personal way. An English friend lived with a same-sex partner who was Ghanaian. When the pair lived in Ghana, they were part of a larger extended family and there was little discord. But the relationship became difficult when they moved to England, in part because the Ghanaian could not handle being identified as a gay man. He was, of course, Charles said, but only in terms of our cultural categories. He functioned as he had always functioned, but he was perceived differently. The fact of naming was very difficult. The norms of the church A Gospel position that includes but genuinely transcends cultural differences is the Holy Grail of this conversation about sex. Shared core Gospel values might be used to contextualize the debate in a less confrontational way. But the search reveals that it is not only global cultures that blind adherents to the real sources of their emotions and theologies but the culture of the global church as well. “Not one clergy I have spoken to has any sense of why we are offending the southern hemisphere,” reports an Anglican priest who has served the Episcopal and Roman Catholic churches as a resource on sexual matters. “They just talk about disturbing the unity.” Back home in America, regardless of the emotional or psychological roots of some of the arguments against ordination of homosexuals, the issues are always framed theologically. “It’s scripture and tradition,” states another Episcopal priest. “The arguments are predictable and come from those who consider themselves the defenders of the orthodox faith. Jesus came not to destroy the law but to fulfill it ... Paul’s lists of sinful behaviors .... it’s all about order and authority,” he explained. “It’s incomprehensible to me. Isn’t Jesus enough? I ask them. Isn’t Jesus a sufficient center for the church? “They just look at me. The issues for them are doctrinal and have to do with the sanctity of marriage and the definition of order. It hearkens back to the Thirty-Nine Articles, which are foundational for the Anglican church. The articles say that the scriptures are sufficient for salvation and nothing ever needs to be added. Of course they mean scripture as interpreted by them. Any other interpretation, any notion of an evolving rather than static faith, is a departure from God’s will and the authority of the church. So other interpretations of scripture or tradition are condemned. “You can understand why, from their point of view. If other interpretations are allowed, then nothing is legitimate or authoritative and it all turns into chaos. Then where does the authority come from?” For most Anglicans, the unity of the communion is based on a shared interpretation of a tradition that allows for complexity and diversity without the necessity of resolving all issues in doctrinal terms. The Roman Catholic church insists on a doctrinal unity that is alien to the Anglican ethos. But in both institutions, the implicit cultural norms of the church itself, those unwritten but widely known rules that govern how an institution in fact acts and behaves, are at the core of the sexual conversation. Yet those norms are seldom discussed explicitly. Theologians such as John Spong, retired Episcopal bishop of Newark, who have long advocated a progressive approach to sexual matters or who deconstruct their own theological arguments are considered fringe elements. That’s not surprising. The hierarchical structure of the church and the way clergy are promoted is very much like the military. A study of military promotion revealed that the inclination to change anything in the institution declines in direct proportion to one’s rank, so those elevated to positions of authority are committed to preserve the institution and its norms. Damage control replaces a passion for justice. In that regard, the church is no different from any other institution hesitant to engage in meaningful self-critique, but the absolute nature of its claims make that lack of authenticity and courage more conspicuous and, some would say, more damning. The current struggle over sexuality is a mirror into which all Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant churches might look. Perhaps the current troubles of the Anglican church can serve as a reflecting shield in which we can all look at the Medusa head of reality and say what we see without being turned to stone. Richard Thieme is a writer and former Episcopal priest. National Catholic Reporter, December 12, 2003 |