Issue Date: December 26, 2003

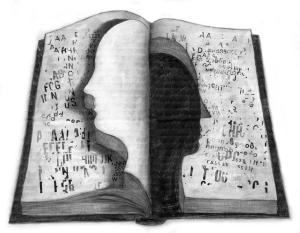

By JOHN L. ALLEN JR. Fueled by fear of losing its identity, today’s Catholic church finds itself embroiled in a war about words. Language -- not merely tired debates over Latin versus the vernacular in the Mass, but deeper questions about how much terminology the church can absorb from the culture without jeopardizing its message -- has become a primary battleground for one of the mega-debates in global Catholicism. In a society sometimes toxic for authentic Christian living, how “different” must Catholics be in order to remain true to themselves? Among the ironies of this language debate, some observers say, is that Pope John Paul II, who seems to suffer little fear about identity himself, and who boldly employs the argot of the broader culture, has nevertheless set forces in motion inside the church at odds with his own vision. Language forms the leading edge of an impulse toward clear boundaries that in the early 21st century cuts across a wide spectrum of issues inside Roman Catholicism, from how “Catholic” church-run schools, hospitals and other institutions ought to be, to the limits of dialogue with other churches and faiths. In an increasingly globalized, homogenized world, many social critics say this concern over identity is by no means misplaced. It reaches down into the lives of average Catholics, prompting young people to seek movements where they can develop a robustly Catholic sense of self, and adults to dust off devotions all but mothballed a generation ago. Given what linguists and social psychologists say -- that language influences how people think -- if the church adopts more specialized speech under the pressure of these identity concerns, it will inevitably promote a more separatist, self-enclosed stance vis-à-vis the culture. Supporters say such a shift will make Catholics more sure of who they are; critics worry it will impede them from explaining that to anyone else. Examples of today’s wars over words:

In some ways, the church has been agonizing over culture since Tertullian in the third century demanded to know what Athens had to do with Jerusalem. The modern form of this debate was set off by the optimistic, culture-embracing document Gaudium et Spes (“The Church in the Modern World”) at the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), which insisted that the joy and hope, the grief and anguish of humanity must also touch the church. What exactly that means is still contested. Richard Gaillardetz, a prominent lay Catholic theologian at the University of Toledo in Ohio, told NCR that worries about distinctiveness reflect the collapse of an earlier model. “Catholicism’s sacramental view of the world … means it is fated to hold together twin affirmations: 1) the uniqueness of God’s revelation in Jesus Christ, exhibited in the teachings, practices and symbol system of Catholicism, and 2) the intrinsically graced character of the world and human existence. During the time in which Christendom flourished, the tension between these two did not seem so great. The church was patron to both art and science and it engaged readily in political discourse. “Today,” Gaillardetz says, under the impact of pluralism, fragmentation and tribalism, “we are a long way from that confident synthesis.” Among the thinkers raising questions about language, albeit with different emphases, are prominent Catholics such as Alasdair MacIntyre, David Schindler, Tracey Rowland and Robert Kraynak, as well as Anglican intellectuals John Milbank and Catherine Pickstock and their “radical orthodoxy.” Pickstock’s 1998 book After Writing: On the Liturgical Consummation of Philosophy as well as Rowland’s Culture and the Thomist Tradition explicitly connect liturgy with the other language debates. Some prominent members of the Catholic hierarchy are supportive, including American Cardinal Francis Stafford, head of the Apostolic Penitentiary in Rome. At a November conference on St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Stafford said: “The explosive problematic following the Second Vatican Council was the naïve optimism of the council with regard to the culture, as expressed in section 53 of Gaudium et Spes. A much more sophisticated critique is necessary.” The debate over language first broke out in the context of the liturgy, and it is where those pushing for a distinctive Catholic argot have scored their biggest victory to date. Capping years of controversy, the 2001 Vatican document Liturgiam Authenticam decreed a shift to a more “sacral” vocabulary in worship, closer to the original Latin. Benedictine Fr. Jeremy Driscoll, an American liturgical expert, provided NCR with some examples, based on a comparison of proposed prayers for the Mass from the International Commission on English in the Liturgy and Driscoll’s own alternatives. In the following instances, the ICEL translation from the Latin is first, Driscoll’s second.

Taken individually, no one of these phrases works a revolution, Driscoll said, but cumulatively they will color how Catholics worship (and thus how they think). Liturgiam Authenticam means that something like Driscoll’s suggestions will likely become the norm. In politics, there is an analogous tendency to question the use of secular terms and categories. In a Dec. 6 interview following a papal audience to present a congressional resolution honoring John Paul’s 25th anniversary, U.S. Congressman Thaddeus McCotter, R-Mich., a Catholic with a strong philosophical background, surprised reporters by saying he refused to use the term values. “I don’t use it unless I’m referring to Nietzsche, because that’s where values derive from,” McCotter said. “The Catholic church is based on verities, not values. Modernity is based on values, meaning your individual perception of reality and the morals that you posit. They are subconsciously Nietzschean. The Catholic church is decidedly anti-Nietzschean.” Some Catholic thinkers likewise challenge human rights because the phrase comes from Western democratic liberalism, reflecting its individualism. Others caution against the term dignity since it stems from the German idealist Immanuel Kant. (Such doubts about invoking human dignity were heard at Vatican II.) Bishop Anthony Fisher, an auxiliary of Sydney, Australia, has drawn a comparison between the debate over political terminology and the 17th-century Chinese Rites controversy. In a November interview with NCR, he said both raise the question of how far the church should go in adopting a cultural idiom. Fisher said that although he has used the vocabulary of human rights, he finds himself “increasingly uncomfortable” with it. Among Catholic philosophers, an influential chorus argues that the church should resist the vocabulary of a modern philosophical movement known as personalism, which prizes subjective experience. The movement is derived from thinkers such as Edmund Husserl and Max Scheler, in turn influenced by Kant. The father of the Catholic form of personalism was Emmanuel Mounier, later adapted to “Thomistic Personalism” by French philosopher Jacques Maritain. Kraynak has described this as a kind of “Kantian Christianity.” “It has a tendency to get out of control,” Kraynak writes, “to be misunderstood by people who are constantly bombarded by ‘secular liberalism’ as opposed to ‘Christian liberalism,’ and who easily forget that human dignity does not lie in autonomy or personal identity but in the possession of an immortal soul with an eternal destiny, permitting only conditional notions of freedom and rights.” The answer proposed is usually the recovery of some form of Thomism, whose concepts and vocabulary were explicitly inspired by Catholicism. Herein lies a great irony of the language debates, because perhaps the foremost exponent of Catholic personalism in the 20th century is none other than Pope John Paul II. In 1962, Karol Wojtyla’s major philosophical work, The Acting Person, attempted a synthesis of Aquinas with Scheler and Kant. Wojtyla was also one of the contributors to Gaudium et Spes. No public figure has employed the terms rights, values and dignity more than John Paul. Just Dec. 12, in remarks to newly accredited ambassadors to the Holy See, John Paul referred to “the universal values of human existence,” “moral principles and values” and “the universal values of solidarity, justice and freedom.” The pope also spoke of “fundamental human rights” and “the dignity of the human person.” The pope’s vocabulary has not always gone down well, and in a surprising number of instances, resistance comes from forces inside the Catholic church that John Paul has encouraged. “Those who feel uncomfortable with John Paul’s use of values have done their best to minimize or nullify its importance,” Legionaries of Christ Fr. Thomas Williams observed in an April 1997 essay in First Things. “Some have denied the fact outright, such as the Catholic League’s well-intentioned ad in the Oct. 2, 1995, edition of The New York Times, which stated that ‘they speak about values, you speak about virtues.’ While John Paul does speak abundantly about virtues, to say he doesn’t speak of values is patently untrue,” Williams wrote. Williams has written a book arguing that the language of human dignity and rights is not only compatible with classical Christian thought, but actually depends on it. The forthcoming book is Who Is My Neighbor? Personalism and the Foundations of Human Rights (Catholic University of America Press). In a Dec. 12 interview with NCR, Williams acknowledged that some Catholics who see themselves as faithful to John Paul, and who have been favored under his papacy, nevertheless do not seem to share his optimism about “baptizing” words and concepts drawn from non-Christian contexts. “How many people have really taken the council’s vision of church and world, as Wojtyla understands it, to heart?” Williams said. “It’s definitely a small minority.” Has John Paul set the stage for his approach not to survive his pontificate? “That’s a legitimate concern,” Williams said, arguing that despite media stereotypes that the pope has appointed a series of like-minded clones, in fact the number of senior officials who share his approach on matters of vocabulary and culture is relatively small. Williams said he takes heart from the grass roots -- young Catholics who he believes have assimilated John Paul’s vision, members of what he called the “World Youth Day” generation. The University of Toledo’s Gaillardetz said that whatever comes next, the proper response to concerns about identity is not retreat into a linguistic enclave. “An authentic and rich reappropriation of Catholic identity should never take us away from the world,” he said, “but lead us deeper into it, confident that God is already there.” John L. Allen Jr. is NCR Rome correspondent. His e-mail address is jallen@natcath.org. National Catholic Reporter, December 26, 2003 |