Issue Date: January 30, 2004

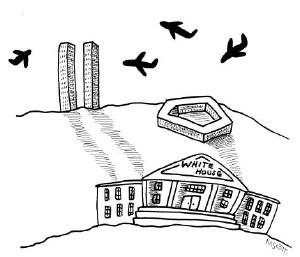

Author accumulates evidence of inaction, ignored warnings By ROSEMARY RUETHER Until recently I dismissed the suggestions that the Bush administration might have been complicit in allowing 9/11 to happen as groundless “conspiracy theory.” I regarded the federal investigative bureaucracies as suffering from a “lock the barn door after the horse has escaped” syndrome. American government agencies seemed to me to be full of repressive energy and exaggerated overreach after some atrocity had occurred, but remarkably incompetent when it came to preventing something in advance. There is no question that the Bush administration has profited greatly from the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, but I did not imagine that it could have actually known they were being planned and deliberately allowed them to happen. Thus it was with some skepticism that I agreed to read the new book written by David Ray Griffin, a process theologian from the Claremont School of Theology in Claremont, Calif., that argues the case for just such complicity. This book, The New Pearl Harbor: Disturbing Questions about the Bush Administration and 9/11, is due for release this month. Griffin admits that he too was skeptical toward such suggestions until he began to actually read the evidence that has been accumulated by a number of researchers, both in the United States and Europe. As he became increasingly convinced that there was a case for complicity, he planned to write an article, but this quickly grew into a book. The first startling piece of evidence that Griffin puts forward is establishing the motive among leaders in the Bush administration for allowing such an attack. Already in 2000 the right-wing authors of the “Project for the New American Century: Rebuilding America’s Defenses” opined that the military expansion they desired would be difficult unless a “new Pearl Harbor” occurred. They had outlined plans for a major imperial expansion of American power that included a greatly increased military budget and invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, primarily to secure oil supplies but also to control the region generally. But they believed that the American people would not have the will for such actions without some devastating attack from outside that would galvanize them through fear and anger to support it. In short, they had already envisioned facilitating a major attack on the United States in order to gain the public support for their policy goals. Griffin then shows the considerable evidence that the Bush administration knew in advance that such an attack was being planned, despite claims by the administration that such an attack was completely unanticipated. As early as 1995 the Philippine police conveyed to the United States information found on an al-Qaeda computer that detailed “Project Bojinka,” which envisioned hijacking planes and flying them into targets such as the World Trade Center, the White House and the Pentagon. By July 2001 the CIA and the FBI had intercepted considerable information that such an attack was planned for the autumn. Leaders of several different countries, including the Taliban in Afghanistan, as well as leaders of Russia, Britain, Jordan, Egypt and Israel, conveyed information to the United States that such an attack was being planned. It appears not only that all these warnings were disregarded, but that investigations into them were obstructed. The actual events of Sept. 11 leave many puzzling questions. Standard procedures for intervention when a plane goes off course were not followed in the case of all four airplanes. Within 10 minutes of evidence that a plane has been hijacked, standard procedures call for fighter jets to intervene and demand that the plane follow it to an airport. If the plane fails to obey, it should be shot down. There was time for this to happen before the plane was over New York City in the case of the first jet and more than ample time in the case of the second. Moreover, when the order was finally given to intervene, it was not to McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey, 70 miles from New York City, but from Otis Air National Guard in Cape Cod, Mass. Griffin also examines unexplained issues about the other two planes. Eyewitnesses and on-site evidence suggest that a missile or guided fighter aircraft, not a large commercial plane, crashed into the Pentagon. Moreover the part of the Pentagon that was hit was not where high-ranking generals were working, but an area under repair with few military officials. Flight 93 was the only plane shot down, although only after it appeared that passengers were on the verge of taking control. Griffin also examines the conduct of President Bush on that day, giving considerable evidence that he knew of the first crash immediately after it happened but delayed his response for about half an hour, nonchalantly continuing with a photo op with elementary schoolchildren. These are only a few details of the myriad data that Griffin assembles to show that not only did the Bush administration have detailed information that such attacks were going to occur on Sept. 11 and failed to carry through protective responses in advance, but that it also obstructed the standard procedures to intervene in these events on the actual day it happened. Griffin concludes the book with some considerable evidence of the way the Bush administration has obstructed any independent investigation of 9/11 since it occurred, both withholding key documents and insisting that the official investigation, when it was set up, limit itself to recommendations about how to avoid such an event in the future, and not focus on how it actually was able to happen. Griffin writes in a precise and careful fashion, avoiding inflammatory rhetoric. He argues for a high probability for the Bush’s administration’s complicity in allowing and facilitating the attacks, based not on any one conclusive piece of evidence but the sheer accumulation of all of the data. He concludes by calling for a genuinely independent investigative effort that would examine all this evidence. He plans to send the book to the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States (called the Kean commission after Thomas Kean, its chair), although Griffin expresses doubts about the commission’s independence. I found Griffin’s book both convincing and chilling. If the complicity of the Bush administration to which he points is true, then Americans have a far greater problem on their hands than even the more ardent antiwar critics have imagined. If the administration would do this, what else would it do to maintain and expand its power? Rosemary Ruether is the Carpenter Professor of Feminist Theology at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, Calif. National Catholic Reporter, January 30, 2004 |