Issue Date: February 6, 2004

Reviewed by TOM ROBERTS The church should read this book. Not because it contains startling new revelations and certainly not because it is uplifting or edifying. It should be read because it will train our focus, in these days of reports and audits, on what we must consider -- church leadership and accountability. It is a must-read because it pulls together, as is only possible in a reported book of this length, the clear evidence of how deeply ingrained is the culture of clerical secrecy that allowed the scandal to flourish. It makes clear that no matter how many new reports and norms are issued, no matter how many episcopal apologies are stacked up amid the wreckage of the crisis, the only real way out of the current mess is to institute bold new mechanisms for establishing transparency and for holding church leadership accountable. Both Jason Berry and Gerald Renner are respected journalists whose careers encompass writing and reporting on myriad subjects but who are probably most widely known for the groundbreaking work each has done in unearthing the clergy sex abuse crisis and the culture of clerical secrecy. By way of full disclosure, their work, individually and as a team has appeared in NCR. Berry’s career is inextricably linked to NCR; his reporting constituted the major contribution to the earliest reports of the sex abuse scandal nearly 20 years ago in these pages. This book is a dramatic telling of the deeper story of the sex abuse crisis that has gripped large segments of the church for the past two decades and that has hit the wider culture most forcefully in the two years since publication of The Boston Globe’s investigative pieces. Those stories led both to a flurry of activity aimed at dealing with the crisis and to the ouster of Cardinal Bernard Law. The story is told primarily through the careers of Dominican Fr. Thomas Doyle, a whistleblower who early on urged the bishops to listen to the victims and to stop hiding abusive priests, and that of Mexican Fr. Marcial Maciel Degollado, founder of the Legion of Christ religious order. Maciel has been accused of sexually abusing seminarians. Under the norms enacted in the United States, given such accusations, he would have been removed from active ministry months ago. However, he remains not only a priest in good standing but a revered figure in Rome who has received clear signs of papal approval.

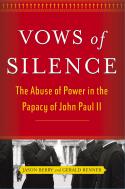

Catholics and others seeking some reason for hope might find it in the unbending integrity of Doyle. He was on a fast career track to a position of influence in the church when he began learning of the early reports of sexual abuse of children by priests. A canon lawyer who taught at the Catholic University of America and worked in the office of the pope’s representative to the United States in Washington, he knew the ropes, what was expected, how to protect the institution. Yet he made a fundamental decision -- one not too many in the clerical ranks made when confronted with the sex abuse scandal -- that he would not be part of the cover-up and deceit. His story, though well known in the broad outlines, is told here in remarkable detail and documentation. As the writers describe Doyle’s moment of reckoning: “It had been 15 years since his ordination. He loved the giving of Christ’s Word in ministry, the joy of sharing the sacraments. He did not want the structure with all its byzantine conflicts and egos to wreck his vocation. There were many victims, too great a pent-up rage. Unable to persuade the hierarchy that a torrent of violations would unleash volcanic winds, he repeated words that became a prayer: This is evil. I am going to help those who have been harmed by this evil because that’s what a priest should do. This is what I believe you want, Lord. Help me do it right.” Vows of Silence is a disturbing tale of who is out of and who remains in Vatican favor, a portrait showing that the same system of secrecy and protection that allowed the sex abuse crisis to overrun the church in the United States is still in place at the highest levels in Rome. There is a telling detail in the fact that Berry’s first book, the 1992 Lead Us Not Into Temptation, is subtitled Catholic Priests and the Sexual Abuse of Children, and the latest on the subject, Vows of Silence, is subtitled The Abuse of Power in the Papacy of John Paul II. Those titles reflect the trajectory and, if you will, evolution of what began as a story of scandal involving priests and children and has become a tale of abuse of power. That evolution seems to escape the understanding of the members of the hierarchy most responsible for the perpetuation of the scandal: those who first acted to save the reputation of the priests involved, and who next re-victimized the victims by refusing to hear them and by going after them with every legal means available, and who finally broke trust with the wider community by secretly raiding the church’s treasury to buy the silence of those abused. Vows of Silence will begin arriving in bookstores about the same time as the release of two reports, one dealing with the causes of the crisis and the other with the dimensions of the crisis as illustrated by the number of priests involved, the number of victims and the amount of money paid out in settlements and legal costs. As beneficial as such timing might be in terms of marketing strategy, it will also be significant for the counterweight the book will provide to those tempted to see the reports as a logical end to the crisis. It is not unusual today to hear the crisis framed in the two-year span that began with the Globe’s exposé of archdiocesan documents that showed, in the language of church leaders themselves, how deeply involved the hierarchy was in protecting priest predators and in ignoring and re-victimizing the priests’ victims. Since then, of course, the bishops have gone through the bizarre meeting in Dallas in June 2002, the negotiation with Rome over new norms governing the disciplining of accused priests and, finally, the attempt to regain credibility through the establishment of the National Review Board and the Office of Child and Youth Protection. However, what Doyle and others know is that the documents resulting from those efforts will, at best, contain information that is self-reported by bishops who fought in every way for nearly 20 years to keep such information hidden. At one point early in the book, the authors quote from a 1988 letter that Bishop A. James Quinn, then an auxiliary in Cleveland, wrote to then-papal representative (and now Cardinal) Archbishop Pio Laghi. Quinn disparages the work of Doyle and a lawyer, Ray Mouton, who with psychologist and priest Michael Peterson, wrote an earlier report containing startlingly accurate warnings about the extent of the crisis and its long-term effects on the church. In his letter, Quinn confidently states, “The church has weathered worse attacks, thanks to the strength and guidance of the Holy Spirit. So, too, will the pedophilia annoyance eventually abate.” Maddening as such sentiments may now seem, it is not beyond reason to suggest that Quinn spoke for a considerable number, if not the majority, of bishops at the time, and that his attitude represented the prevailing feelings within the institution. Doyle, who once knew such language and how to play the game, developed a rather coarse view of those who would protect the institution at all costs. He soon became a principal witness against the church and its policies, and in one conversation with a lawyer handling sex abuse cases, said, “If the bishops dealt with the problem publicly, for the benefit of victims, we wouldn’t have this crisis. They don’t know how to be honest.” In 1999, some 15 years after he had first learned of the growing crisis and two years before the scandal exploded anew in Boston, Doyle wrote in The Irish Times, as quoted in Vows of Silence, “Priests express their embarrassment to appear in public dressed in clerical garb. The pope is ‘personally and profoundly’ afflicted and worries that the acts of the abusers will taint all men of the cloth. The truth is that most people could care less about their pain and embarrassment. … Something is wrong and that wrong can’t be sandpapered away by emotional expressions of personal hurt or self-righteous expressions of rage at the abusers. It is precisely this clerical narcissism that produced the crisis in the first place.” Clerical narcissism might be the best phrase for describing the career of Maciel, who swore to secrecy those he allegedly abused and who frightened young doubters in his ranks with the mantra, “Lost vocation, sure damnation.” Maciel, whose checkered career included expulsions from two seminaries and being turned down by six, used family connections -- two Mexican bishops -- to reach ordination. They allowed him to be tutored privately and finally ordained him after “far less training than the average diocesan priest or member of a religious order in most countries of the world.” Maciel showed himself a genius at raising money. He is described as charming and persuasive. He cast his various difficulties -- for instance, Vatican inquiries into possible drug addiction and presumably over rumors of his sexual abuse of youngsters -- in terms of mighty, holy struggles against unholy enemies. But in time some of his accusers would go public, eight in all, former seminarians and priests who inhabit responsible professions and jobs, eight men who had similar experiences with Maciel at different times and whose stories convinced local church officials as well as some officials in Rome that their cases deserved further scrutiny. But the cases against Maciel would only go so far. As one high-level canon lawyer, who was convinced the case should go forward, finally told one of the accusers, “Perhaps it was better for eight innocent men to suffer than thousands of people losing their faith.” It was, as others said behind Vatican walls, “a delicate matter.” Berry and Renner reconstruct the case against Maciel with interviews of former members of the order, as well as the eight accusers. They also continue the reporting they have done elsewhere on the activities of the order, particularly in the United States, where it has become known for taking over schools and becoming a presence in certain parishes. Nearly always, controversy follows the schools, with Catholics previously dedicated to the cause feeling manipulated and whipsawed by Legion tactics, which, in the echoes of the founder, are often secretive and bullying. Their account is fact-filled and riveting, moving from religious houses in Spain and Mexico to the halls of the Vatican bureaucracy. And they get to the voices that often go unheard, Catholics who bought into the Legion program only to be shocked to see trusted teachers and administrators intimidated and fired, strange religious practices and extreme regimentation put in place. In other instances, Catholics complained that the Legion and its lay arm, Regnum Christi, simply misrepresented their intents. Said one North Carolina Catholic: “I believed in what the Legion espoused. I was energized by the thought of being a part of the re-evangelization of the Catholic faith. I do not subscribe to the implementation of their plan. Deception and other improprieties should never be a mainstay of any mission of Christ.” One bishop, James A. Griffin of Columbus, Ohio, looked beyond papal approval of the order and its founder and banned the Legion and Regnum Christi from his diocese. In October 2002, Griffin banned Regnum Christi meetings from parish property and notified Catholics that he had already signed an agreement with the provincial of the order stating “that their priests are not to be active in any way in the diocese of Columbus.” Regnum Christi was banned from promoting any programs for young people or adults. The Legion and other Maciel supporters are given ample space in the book to refute the claims, but the order, sadly, comes up with a tired and inadequate response: All of the accusations are the work of some grand conspiracy of former malcontents. Others who defend Maciel and, more often, the order, have never spoken to the accusers and cannot have considered seriously the detailed accusations. Anyone who does approach them seriously, given what we have come to know about the behavior of both abusers and their victims, would have to stretch reason to the breaking point to conclude that the Maciel case is not worthy of deeper investigation and adjudication. Berry and Renner make a convincing primae facie case that the accusations against Maciel should be taken seriously. There’s no smoking gun, of course, and it’s possible that there’s more to the story. Yet this is precisely the point: If Maciel is innocent, then the Vatican is doing him no favors denying his accusers their day in court. And the Vatican does the wider church no favor by reinforcing the perception that no reliable mechanism exists for holding church leadership accountable. Thomas Doyle, the Dominican who did what the bishops in recent months have so profusely apologized for not doing, is still on the outs. One suspects it will be a long time before the bishops will gather to propose honoring one of the few examples of integrity in the sex abuse mess. Maciel continues to enjoy the Vatican’s favor. Meanwhile the details of the case fade in files presumably in some corner of the offices of Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in Rome. The accusers are aging, and those willing to take up the fight fewer by the year. Renner and Berry do us the great service of preserving the details. Theirs is a report that should be added to the others that will come out in late February. Tom Roberts is NCR editor. His e-mail address is troberts@natcath.org. National Catholic Reporter, February 6, 2004 |