Issue Date: February 6, 2004

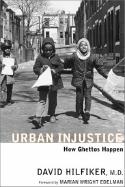

Lutheran pastor' journey, study of ghettos uncover inner-city life Reviewed by DENNY KINDERMAN It was a scene of devastation when I arrived in Cincinnati at the end of the summer of 1967 after my ordination. There were stores up and down Montgomery Road that had been burned out, and a few would be torched the following spring in civil disturbances that would mark the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. I walked the streets, attended neighborhood meetings and joined the clergy group of black, mainly Baptist pastors, trying to figure out what I was to do as a white priest in an unfamiliar setting. I was more attentive to what I might be able to offer than to what I would receive in that African-American neighborhood. But I received nonetheless, with a dawning awareness that I was growing into a spirituality found in the streets and unlikely corners of the community as well as among brother ministers. It is a spirituality that continues to enrich my ministry today in the Back of the Yards neighborhood of Chicago. Two recent books about inner-city life and ministry reveal this “spirituality of the streets” and the background against which the American poor conduct their lives. A tale of transfiguration Lutheran pastor Heidi Neumark’s story of her inner-city spiritual journey takes its title from a prayer of Pius V: “Have mercy on your people, Lord, and give us breathing space in the midst of so many troubles.” When she wrote Breathing Space, Neumark was pastor at Transfiguration Lutheran Church at 156th Street and Prospect Avenue in the South Bronx. Neumark’s own tale of transfiguration is told within the context of the construction on her church. She makes frequent correlations between the building progress on the addition to her church and Teresa of Avila’s The Interior Castle. As part of the renovations, she painted her church doors, offering welcome to all while encountering many doors closed to her and her congregation as they faced a stream of challenges. Neumark ventured beyond the church and into the street, where she found many brothers and sisters who felt unfit to enter through those painted church doors. She takes her readers on a trek through her neighborhood and opens doors into homes, apartments and courtrooms, making the poor seem real to us, giving them faces, names and lives. Readers learn how she gathered together the so-called “nobodies” who became leaders in her church and the South Bronx community. “Some future pillars of the church arrive in ruins,” the author notes. Neumark’s commitment and courage as mother and wife carry over into her role as pastor and community caregiver. Her reflection on malabarriga (Spanish for “evil belly”) during her pregnancy with her son Hans is entwined with the story of her neighborhood and congregation becoming a source of welcome to African-Americans. While balancing the needs of the English-speaking African-Americans in her group, she learned Spanish as the predominant language of her parishioners. Neumark’s description of her experiences is disarming. She holds nothing back -- not her impatience, her anger, her contempt, her frustrations or her fears. Eventually, she reached a point in her life where writing saved her from going over the edge, just as deep breathing brings a calm that shallow breaths cannot attain. This compelling book came from her contemplation about breathing a “world-mothering air,” as poet Gerard Manley Hopkins put it. Simply summed up, we breathe or we die. The ruah of God saturates the pages of Breathing Space, despite the “smoke, gunshots, screams and sirens” that poisoned the air in her neighborhood. Breathing maintains life for flesh and blood, and space affects the quality of one’s life. Breathing space is, then, a matter of life and death. Neumark’s book embraces these realities, transforming dying into breathing and space. Challenging privilege David Hilfiker’s Urban Injustice: How Ghettos Happen paints a compelling canvas of the complex political, social and economic structures that, uncontested, assure the continuance of urban poverty in the United States. In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson created a commission to determine the cause of the riots that had plagued cities each summer since l964. The result was the 1968 Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, called the Kerner Report. It stated that riots were the direct result of racism and poverty, and that great, sustained national efforts would be required to combat racism, unemployment and poverty. “The Millennium Breach,” a document from the Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation, reported 30 years after the Kerner Report that “the rich are getting richer, the poor are getting poorer, and minorities are suffering disproportionately.” Both reports made the statement that the United States consists of two separate societies, one white and the other black.

Since social and political structures continue to offer power to the rich and white, Hilfiker writes in order to challenge those of us who live in privilege. He writes from his experience as a white physician who has worked with homeless and HIV-positive men in Washington for nearly 20 years. This experience led him to probe deeper the easy condemnation of the poor. We too readily write off those who live in the inner city, especially African-Americans and Hispanics, as lazy or conniving or unable or unwilling. Hilfiker refuses to be guided by such simplistic answers. Urban Injustice reports Hilfiker’s discovery that beneath unacceptable behaviors lie wholesome desires often frustrated. He insists that there are forces beyond any individual’s control -- including social and historical structures -- that place one in the midst of poverty, regardless of one’s personal behaviors. The evidence is compelling. The author carefully considers connections between health and poverty, between working and welfare, between prison and rehabilitation programs, pointing out the myths that often surround these subjects. For example, building more prisons may be a boost to employment in local communities, but filling them through “three strikes” and “mandatory sentencing” laws is missing the goal of crime prevention, to say nothing of rehabilitation. Hilfiker’s reflections help one understand why those who are the “beneficiaries” of various programs still seem to fall short of expectations. The question to ask, he contends, is whether the program is designed to eliminate or alleviate poverty. Do these programs offer benefits that no one can live on while focusing attention on people as “deserving” or “non-deserving”? After describing failed solutions and the odds against success, Hilfiger proposes ways to end poverty as we know it. He recommends new programs for integrated housing, equitable education opportunities and universal health coverage through a “single-payer plan.” He challenges us to consider an alternative to what has been tried. But ending poverty would mean ending economic and racial segregation. In the face of blatant inequality, the myth of “separate but equal” persists. Hilfiker’s clear, polemic-free style brings readers to fresh awareness rather than a sense of guilt. He includes an annotated bibliography and some worthwhile Web sites. The book would serve well as college course material. However, it challenges everyone, not just scholars. Both of these fine books challenge us to decide how we will be present to those who live outside the world of privilege. After we become aware of how ghettos happen, it is up to us to decide our role in Christian outreach. Precious Blood Fr. Denny Kinderman ministers to poor people in Chicago. National Catholic Reporter, February 6, 2004 |