|

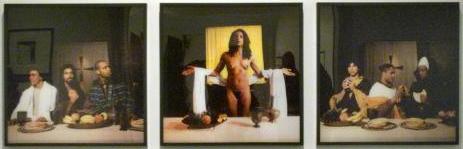

Issue Date: February 20, 2004 The bawdy art of Catholics Catholic imagination shapes contemporary art in daring, sometimes shocking ways By ELEANOR HEARTNEY If you think about the high-visibility art controversies occurring in the United States during the last 15 years, it’s a striking fact that nearly all the artists involved were raised Catholic. These artists include Robert Mapplethorpe, whose 1989 retrospective nearly shut down the National Endowment for the Arts and brought a respected museum director to trial for “pandering obscenity”; Andres Serrano, creator of the infamous “Piss Christ”; Karen Finley, the so-called “Chocolate-coated woman”; Robert Gober, whose chapel installation at a Los Angeles museum became known as the “Virgin impaled on a pipe”; Chris Ofili’s supposedly dung-smeared Virgin Mary at the Brooklyn Museum of Art; and Renee Cox’s photographic recreation of da Vinci’s Last Supper with her own nude body in the central role as Christ. The most recent controversy is currently unfolding at Washburn University in Topeka, Kan., where artist Jerry Boyle is exhibiting a sculpture of a bishop whose miter, some say, resembles a penis.

Why are so many controversial artists from a Catholic background? The usual assumption (something I heard again for the umpteenth time at a recent dinner party) is that these artists are engaging in a full-scale rebellion against their childhood indoctrination. My research suggests that something far richer and more complex is going on. The artists above differ widely in their public stances on Catholicism. Their attitudes range from angry rejection (most pronounced in gay artists stung by Catholicism’s position on homosexuality) to anguished questioning to serene acceptance and belief. But despite such differences, all acknowledge its considerable influence over their artistic imaginations. Significantly, the form that influence takes is remarkably consistent. Whether or not they use overtly Christian symbolism, these artists all create work that focuses in some way on the physical body, its fluids, its processes and its sexual behaviors. I believe this body focus can be traced to Catholicism’s incarnational emphasis. Christ’s status as “Word made flesh” infuses the Catholic faith with corporeality, creating a situation in which the human body serves as the portal through which humanity makes its approach to God. Catholicism -- to a much greater degree than Protestant versions of Christianity, which evolved to counter Catholic “decadence” and carnality -- relies on the sensual experiences of visual art to convey the truths of religion. One need only contrast the theatrical spectacle of a Baroque cathedral with the plain white simplicity of a Congregational church to grasp the difference between these approaches to faith. As an art critic from a Catholic background, I’m interested in what connection might exist between artists’ religious training and the potentially inflammatory nature of their work. In the midst of my explorations on this subject, I discovered Andrew Greeley’s The Catholic Imagination. This book cogently encapsulated what I was discovering. Greeley argues that Catholicism sees this world as an extension, however flawed, of the next, while Protestantism posits a more absolute break between the realms of body and soul. According to Greeley, “The Catholic imagination in all its many manifestations … tends to emphasize the metaphorical nature of creation. … Everything in creation, from the exploding cosmos to the whirling, dancing, and utterly mysterious quantum particles, discloses something about God and, in so doing, brings God among us. The love of God for us, in perhaps the boldest of all metaphors (and one with which the church has been perennially uneasy), is like the passionate love between man and woman. God lurks in aroused human love and reveals himself to us (the two humans first of all) through it.” This carnal, even sexualized imagination helps explain why artists from Catholic backgrounds are so often mired in controversy. A “Catholic imagination” tends to produce art works that deal with sexuality and body in ways that may seem offensive, even sacrilegious and blasphemous in a culture shaped by a more Protestant sensibility. Obscured in the fray is how close such work often is to canonical examples of devotional art and literature. One finds close parallels between the supposed obscene and blasphemous representations of contemporary Catholic artists and the almost shocking eroticism of Bernini’s St. Teresa, the use of sexual metaphors in Bernard of Clairvaux’s Sermons on the Song of Songs and the mingling of physical and spiritual pains and pleasures in Dante’s Inferno.

Cultural resistance to works of these body-conscious artists can be partly explained by the chasm between Catholic and Protestant sensibilities. However, conservative Catholics are also among these artists’ most vocal detractors. Over the years, these critics have included William Donohue of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights, former New York City Mayor Rudolph Guiliani and political commentator Patrick Buchanan. I puzzled over this fact. In some cases, the underlying motives were clearly political, as when Guiliani made his opposition to Ofili’s “sick” art part of his strategy to appeal to conservative Catholic voters. But these responses also reflect deep divisions within American Catholicism with respect to such social issues as homosexuality, reproductive rights and feminism. And, given the absence of such art controversies in supposedly far more conservative Catholic countries such as Spain and France, I can’t help feeling that these flare-ups also grow from a pervasive discomfort with the body that has seeped into American Catholicism from the underground current of our nation’s Puritan heritage. Warhol, Mapplethorpe, Serrano In tracing the Catholic influence on contemporary American art, one could do worse than to begin with Andy Warhol. It often surprises people to learn that Warhol was a practicing Catholic, that he went to Mass regularly, though in deference to his “sinful” state as a homosexual, he sat in the back and declined to take Communion. His work is often hailed (or dismissed, depending on the commentator’s viewpoint) as a reflection of the banality of American consumer culture. But, as Jane Daggett Dillenberger suggests in her book The Religious Art of Andy Warhol, Warhol frequently made reference to his Catholic beliefs. A number of works borrow directly from devotional art, most obsessively in the case of his last series, based on da Vinci’s Last Supper. In other cases, Warhol used contemporary images to evoke traditional Christian themes. These include representations of Marilyn Monroe surrounded by a gold halo like a Byzantine icon, portrayals of a solitary electric chair captured half in shadow and suffused with the solemnity of a crucifixion, hypnotic repetitions of skulls, candles and other evocative symbols of spirit and death. Meanwhile, a more underground body of work attested to a more active homosexual life than many of his mainstream supporters might have wished to contemplate. In one such image, a young male bodybuilder is juxtaposed with the image of Christ from the Last Supper, suggesting the conflation of physical and spiritual desire that is a recurring Catholic theme. The slogan emblazoned on this work, “Be Somebody with a Body,” sums up the incarnational consciousness that is at the heart of Warhol’s Catholic imagination. Robert Mapplethorpe, who knew Warhol casually, presents another, more deeply conflicted response to Catholicism. A former altar boy, he grew up to be the darling of the society set, creating elegant photographs of flowers, celebrities and (mostly male) nudes. Like Warhol, he produced a more underground body of works that dealt more directly with his homosexuality. Using the same theatrical lighting and luscious printing that characterized his more public work, Mapplethorpe’s infamous “X Portfolio” lovingly documented the rites and paraphernalia of the gay sadomasochistic lifestyle. When the “X Portfolio” was included in a traveling retrospective that opened just before Mapplethorpe’s AIDS-related death in 1989, right-wing Republicans rushed to condemn the show as an example of “government-sponsored porn.” However, the public perception of Mapplethorpe that lingers from this brouhaha doesn’t do justice to the complexity of his work. Many commentators have pointed to formal aspects of his work that echo devotional art -- the central focus, streaming light, triptych format, even poses borrowed from famous religious paintings. Clearly seduced by the beauty of traditional Catholic art and ritual, Mapplethorpe took issue with Catholicism’s negation of his sexuality. He photographed himself with devil’s horns and merged the iconography of religious art and gay porn. Cast, like Lucifer, out of heaven, he responded by reversing the traditional invocation of physical ecstasy as a metaphor for union with God. Instead, Mapplethorpe used the tropes associated with spirituality to explore the all-encompassing role played by sex in his life. Andres Serrano, the artist whose name seems forever linked with Mapplethorpe’s as a result of their near-simultaneous notoriety, has a much less fractious relationship to his Catholicism. Outside art circles, Serrano is known as the creator of “the crucifix dipped in urine” whose work received a small government grant in 1989. In fact, “Piss Christ,” the offending photograph, exemplifies Serrano’s exploration of the fine line between sacred beauty and earthly manifestations of the profane. His work deals with transformations -- things considered base and lowly (these have included body fluids, raw meat, prostitutes, the homeless and cadavers) are transformed into images that seem touched with divine light. “Piss Christ” belongs to a series depicting banal religious figurines that glow with an unearthly light when photographed through substances like blood, milk, water and urine. These works deliberately play on our discomfort with body processes and secretions, but they also evoke Catholicism’s transformation of substances like Mary’s milk or Christ’s blood into conduits for divine grace. Women artists and Mary My research has also focused on a number of women artists for whom questions of body and sexuality mingle with the mixed messages conveyed by the persona of the Virgin Mary. Mary’s virginity and her motherhood represent the great female ideals, yet, outside her own unique experience, these are mutually exclusive states. Thus, Mary represents a purity that is impossible to emulate.

For artists like Kiki Smith and Janine Antoni, the image of the Virgin Mary merges with social constructions of femininity. They admire the Virgin’s strength but are uncomfortable with her submissiveness. Smith creates figurative sculptures that explore this contradiction. One represents a flayed Virgin Mary, suggesting what she has sacrificed to be the Mother of God. Another presents Mary Magdalene, naked but hair-covered, as she might have appeared during her later days as a hermit in the desert. In this work, Smith recovers the animal sexuality that has traditionally been denied the “reformed” Magdalene. Antoni has worked with lard and chocolate to suggest the dichotomy between purity and sensuality. In some works, she shapes sculptures by gnawing on chocolate and chewing lard, thus literally making the work part of her body. In this way she references both Mary’s bodily connection to her son and the sacrament of Eucharist, in which believers ingest the body and blood of Christ. For artists such as Smith and Antoni, issues of Catholicism and feminism merge. Catholicism suggests that we approach God through our sensate experiences in the world, while feminism challenges masculine assumptions about the superiority of mind over body. Catholics and women have long understood that we grasp the world as embodied creatures. Both remind us that we cannot separate our corporal and spiritual experiences. A wider definition of faith I began exploring the notion of the Catholic imagination during the culture wars of the 1990s, when art controversies provided conservatives with ammunition against federal spending for the arts. In their struggles to come to terms with Catholicism, artists like those discussed here enlarge our understanding of religion’s relationship to the creative imagination. In the process they argue for a more open definition of faith and spirituality. Their work explodes the shibboleth that contemporary art and religion are necessarily at odds. Instead, it turns out that they enrich each other. Without taking the complexities explored here into account, we will fail to understand the deepest aspects of both Catholic spirituality and contemporary art. Eleanor Heartney is an internationally published art critic. She is co-president of AICA-US, the American section of the International Art Critics Association. Her forthcoming book Postmodern Heretics: The Catholic Imagination in Contemporary Art, to be published in late February by Midmarch Arts Press, will expand on the ideas in this essay. National Catholic Reporter, February 20, 2004 |