Issue Date: March 12, 2004

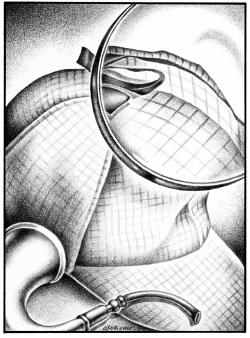

A comparison of today's TV crime dramas with crime novels of the past shows how our culture has changed By RAYMOND A. SCHROTH I had fallen asleep during a post-midnight “Nightline” in my big TV-watching chair and then suddenly I snapped out of it and Oprah Winfrey was in the room. Ted Koppel had lost me, but now, in a replay between 1 and 2 a.m., Oprah had snagged my attention with the corpse of a beautiful woman. I had missed her opening, but the show seemed to be a celebration, from the woman’s angle -- with a real life woman investigator, the star who plays her role, the dead bodies of women in ditches and stretched out on the morgue table, and the mothers of the deceased smiling up from the studio audience -- of the “hottest” show on television, CBS’s “Crime Scene Investigation.” The focus on women’s corpses struck me as macabre, yet it recalls Edgar Allan Poe’s theory that the death of a beautiful woman is “the most poetical topic in the world.” But does the woman’s beauty make the death more tragic or, as on the TV screen, more entertaining? In what seemed the coldest week in the history of the world, I sat home with death, disappearances, dismemberment and detection on several episodes each of “CSI,” “Cold Case,” “Cold Case Files” (a different show), “The Practice,” “Without A Trace” and the feature film “A Perfect Murder.” Both Jacques Barzun and George Orwell have said that the quality of crime fiction reflects the values of its era. Orwell, writing toward the end of World War II, said the popularity of James Hudley Chase’s 1939 No Orchids for Mrs. Blandish, with its torture, rape and suicide, manifested the rise in sadism, power-worship and totalitarianism that brought on the war. A traditionalist like myself prefers the classic Sir Arthur Conan Doyle-Agatha Christie murder mystery format where Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot is summoned to an old country mansion where Sir Bottomley has been found on the library floor with his head bashed in.

Usually the audience is not treated to the sight of the bashed-in head; the detective makes his inquiries and, on the basis of one’s knowledge of human nature welded to a logical mind, brings the drama to a climax. For Holmes, the climax may be a chase across the moors; for Poirot, it’s a gathering of all the suspects in the parlor as the camera scrutinizes every blink, tick and squirm while “the great detective” -- not the “great Belgian detective,” as he reminds his clients -- runs down the list. “CSI,” on the other hand, is written for the cell-phone generation, for those whose overwhelming absorption in e-mail, TV, CDs, DVDs and pocket gizmos that enable them to read mail, call home, write letters and download music and films at the same time, constitute a technology church. As a lab attendant spells out the chemical analysis of an autopsy, the screen erupts in a phantasmagoria of cells, blood vessels and bones like those illustrations in high school science textbooks, accompanied by “vaarrooom” music to remind us that something scientifically awesome has taken place. One episode shown Jan. 15 opens with a man placing the barrel of a gun in his mouth. A beautiful young woman, a photographer’s model, is missing. Her corpse is found buried in the desert where her photographer had taken her for a shoot. The CSI staff analyzes his photographs -- a nude model posed against the dashboard of an expensive car -- only to realize they should have been examining his gun. There were abrasions on her cervix, but no semen. But her DNA was on his gun barrel. We get the picture. Case solved. Another episode the same night opens with the corpse of a beautiful woman doubled up on her kitchen floor. She was a nurse who “liked to party” with the doctors at the hospital. One likely MD suspect, however, has himself been killed, his corpse sliced into little pieces -- including his sexual organs and his face -- and put in plastic bags deposited in a line of dumpsters. Shades of Jack the Ripper: Only a surgeon could so skillfully slice his victim up. Or consider what Holmes says to Dr. Watson in “The Speckled Band,” where the obvious culprit is the violent Dr. Grimesby Roylott of Stoke Moran, who tries to kill his stepdaughters with a poisonous snake to protect his inheritance: “When a doctor does go wrong, he is the first of criminals.” Crime scene and corpse analysis -- check the cut on the body parts -- reveal that the slicer-upper was a left-handed surgeon who used Rogaine. Going bald and going bad. Orwell observes that before World War I, crime stories, not all of which included murder, presumed some kind of moral code; since the war, corpses have piled up and “the most disgusting details of dismemberment and exhumation are commonly exploited.” An episode of “Cold Case Files,” an A&E documentary about forensic anthropology, centers on the rotting corpse of a murdered drifter. To pinpoint the time of his death six years before, we consult the “Body Farm” at the University of Tennessee, a research lab where 30 corpses are allowed to rot in the open air in order to study the timing of their decomposition. It turns out that the flies and maggots stage coincided with the date when the dead man’s friends withdrew money from his bank account. Got ’em. “Cold Case,” on the other hand, appeals to our yearning for closure. One case is literally cold. In the Jan. 18 episode, the corpse of a young boy is found frozen in the snow. A grocery store owner implicates a black boy who had been hanging around with his gang and who then disappeared. Twenty-five years pass and we track down the black suspect, now a drug bum who has abandoned his wife and child. He implicates the parish priest. Is this another exploitation of the “pedophile” crisis in the church? Yes and no. Perhaps the killer confessed his crime to Father under the seal of confession. The police dupe the real killer -- the Irish Catholic bigot grocer who was mad at the boy for stealing glue to give to the blacks to sniff -- by pretending that Father, now “retired” and allegedly free from his seal, has spilled the truth. Occasionally however, a show does more than mirror its time. It slips in a political-moral zinger that makes it about more than just another killing. In a Jan. 15 episode of “Without A Trace,” a character in a law firm tells the police, “I’m not used to the government going through my files.” The cop snaps back, “Under the Patriot Act there’s no such thing as a confidential file.” In a Jan. 11 episode of “The Practice,” a young man is accused of shooting a cop who dies. Wounded in the arrest and confined to his hospital bed, the young man is tortured by the police during his interrogation. As his cries of pain emanate from behind the curtain, the law firm protests to the FBI, challenges the Irish DA, and even interrupts a judge in the midst of a nocturnal adultery, in failed attempts to rescue their client. The black attorney, Eugene Young, who is the firm’s moral center, declares in righteous anger that what is happening in that hospital room is typical of what is happening to American justice at large: Under Attorney General John Ashcroft, “We are becoming a police state.” He might add, a police state that has gone through two wars in three years and in which pictures of corpses neither shock nor surprise. Jesuit Fr. Raymond A. Schroth is Jesuit community professor of the humanities at St. Peter’s College, Jersey City, N.J. His e-mail address is: raymondschroth@aol.com National Catholic Reporter, March 12, 2004 |